Good Reasons Why You May Choose NOT to Use the New Privacy Features in iOS 15

Credit: Apple

Credit: Apple

Toggle Dark Mode

For the past few years, each major new release of iOS had added significant and important new features to empower users to take control of how their information is used online, and iOS 15 is no exception. However, just because these privacy options are there doesn’t mean you have to use them, and in fact, there are some cases where they simply may not be worth the trouble.

Open internet advocate and Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) co-founder John Gilmore once famously said that “the Net interprets censorship as damage and routes around it.” Perhaps, unfortunately, however, the same could be said on the other side about privacy protections.

On the modern internet, most online services lean toward collecting as much data about you as possible, but as scary as that can sometimes sound, it’s truthfully not always a bad thing.

After all, there’s no such thing as a free lunch.

The vast majority of online services that we access on a daily basis don’t require us to spend money out of our pocket. Whether that’s reading sites like iDrop News, watching videos on YouTube, or using free email services like Gmail, various companies provide content and services at no direct charge to the end user.

Instead, the costs of running these services are paid for by advertisers, and these advertisers need data to ensure that they’re getting the most out of their advertising dollars.

To be clear, advertising has always been a data-hungry industry. It’s just that modern technology has made that data more available.

Print newspapers ran ads as their primary source of income for over a century. In print media, the fees you pay to buy or subscribe to your daily newspaper simply covered the costs of physically printing the paper and getting it to the local newsstand or your front door — they don’t even begin to cover the costs of paying journalists and other staff, or even the cost of keeping the lights on at your local newspaper office.

Even though the ads shown in your local paper may have seemed quite random, even 100 years ago, advertisers and publishers were trying to collect demographic data on their subscribers so that they could target their ads in the best places. Even back in the 1950s, advertisers knew that more housewives read the Sunday edition, and would therefore target ads for groceries and household supplies in those particular issues. Similarly, The Wall Street Journal knows that it has a much more affluent subscriber base, which is why it’s the paper that’s more likely to run ads for higher-end haberdasheries and luxury cars.

This isn’t confined to print media, however, nor is it a symptom of the modern internet. Television studios and cable networks discovered the value of this back in the seventies, and by the 1980s were sending out Nielsen boxes to collect demographic data on what kind of TV shows were watched, and who was watching them.

VISA and Mastercard were also collecting data on consumer purchases more than 40 years ago to build demographics that could be sold to data-hungry ad companies. This also became the basis for modern-day customer loyalty programs, which reward you with “points” for your purchases at various stores and other businesses. However, those points are ultimately just a token payment for the data that they’re getting on you every time you swipe your loyalty card at your local Walgreens.

Ultimately, however, the key to understanding the relationship between privacy and online services is to begin treating your data as something with tangible value that you use to pay for the services that you enjoy using.

After all, you are getting something for your advertising data in many of these scenarios. Whether that’s loyalty card points in retail stores, great information on Apple products, or just solid email services, there is a marketplace exchange going on. It’s just that most of it happens more invisibly than simply punching in your credit card number to pay in actual dollars.

To that end, choosing to voluntarily supply some of your personal information to your favourite online sites and services is a great way of ensuring that you can continue to enjoy them in perpetuity.

In fact, this is ultimately what Apple’s privacy features are all about. Apple is not automatically blocking every piece of ad tracking. Instead, it’s giving YOU the choice to determine when and where you’re willing to allow your data to be used.

The point is not to overzealously turn everything off in the hopes of just becoming an anonymous cipher on the internet, but rather to understand the value that you can bring to the table, and give you the free agency to decide where you’re going to spend that currency.

This isn’t even a new problem. We’ve seen this for years with ad blockers. Most give you the choice of where you want to allow ads and where you want to block them, on a per-site basis, and you’ll find that many sites will at least encourage you to turn off your ad blocker to offer your financial support.

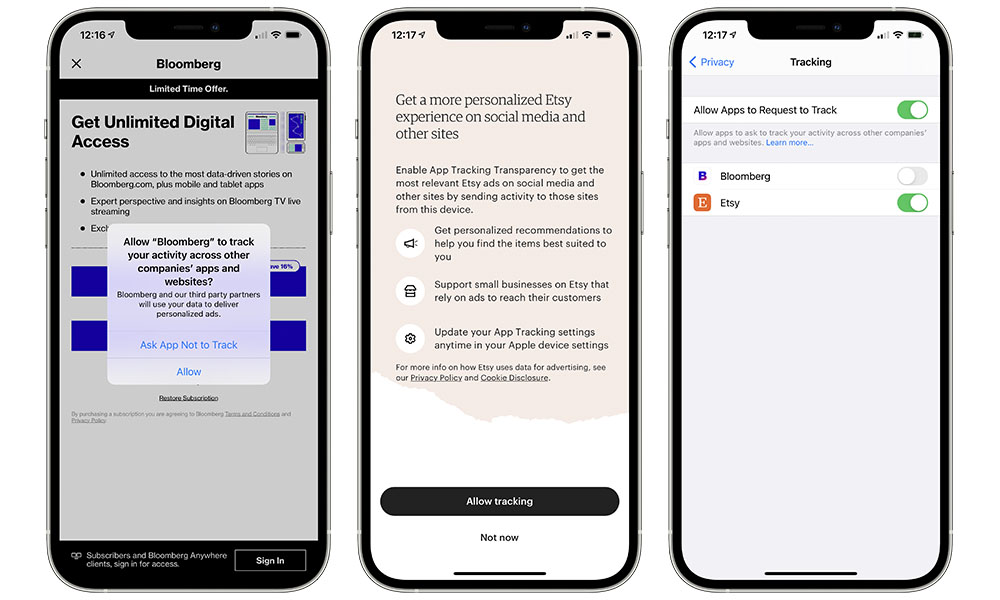

App Tracking Transparency

We first saw this approach most obviously in the App Tracking Transparency feature that was rolled out in iOS 14.5. Despite Facebook’s insistence that the sky was falling, the feature wasn’t about cutting the advertising industry off at the knees, but ensuring that you, the end user, had a say in which apps would be allowed to track your online activity and share it with other apps and websites.

In fact, in our opinion, the App Tracking Transparency accomplished far more than simply offering users the option. Apps and websites were suddenly forced to make a compelling case to try to convince users to opt-in. The power was now in the hands of the consumer to choose which businesses they wanted to support with their data.

In the midst of all of this, it’s also important to remember that advertisers couldn’t possibly care less about you personally. This is not a shady secret agent spy network, but rather simply a way of building a profile that draws meaningful connections between the things you do and the things you’re likely to buy. Advertisers don’t need to know who you are to do this, and the vast majority of this data is collected with complete anonymity.

For example, I know that nobody out there cares what “Jesse Hollington” is doing, but they definitely want to know that I might be one of 87,453 people in Toronto who ordered pizza last Friday, watched Apple’s new Foundation series, and then searched for smoothie recipes on Saturday morning.

They don’t need to know my personal identity to find that information valuable — although of course the more obscure my habits are, the less useful my information will be, since they’re looking for profiles that show major trends that they can market to. If you’re into underwater basket weaving, that’s going to be far less relevant, considering the rather small market for waterproof wicker.

Still, if you want to support your favourite app, or even simply want to get more useful recommendations online, you may very well choose to “Allow Tracking” for those that you know and trust. As an added bonus, you’ll also get more relevant ads.

After all, if you’re going to be looking at ads anyway — and you are — isn’t it much better to see ones for products you might have a chance of actually being interested in?

The same logic applies to Apple’s other new privacy features in iOS 15, which this time around are primarily centered on email.

Hide My Email

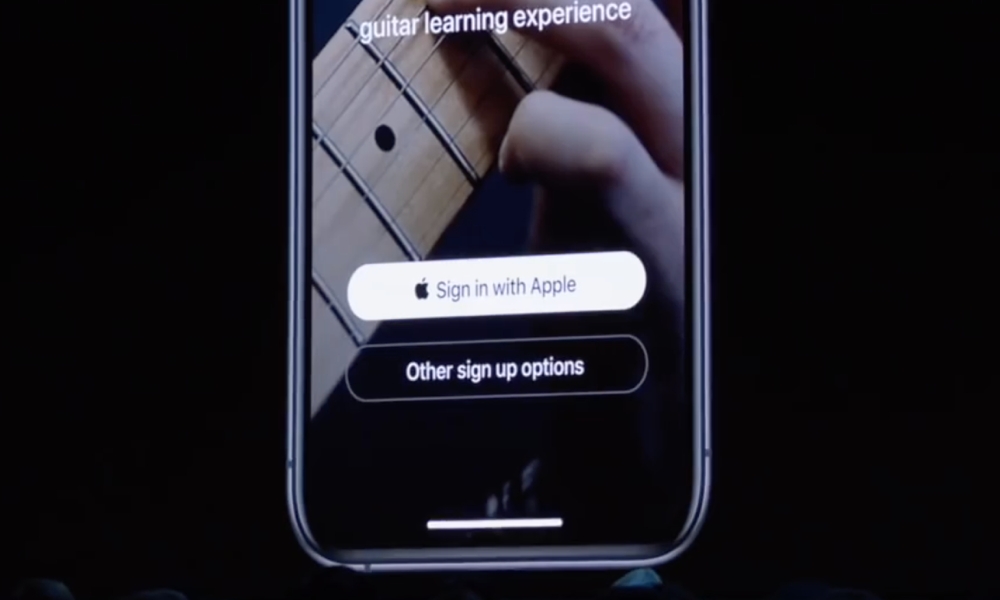

Apple’s new Hide My Email feature actually grew out of Sign in with Apple that came along two years ago with iOS 13. However, we’d argue that the new feature isn’t nearly as important as it was in its more limited incarnation.

Sign in with Apple was all about allowing you to sign in to apps using your Apple ID rather than an email address (or a Google or Facebook account). This was great for privacy, since Apple wouldn’t share any personal information with the app developer, and you also gained the ability to use an anonymized private forwarding address, such that you didn’t even have to give out your real email.

Considering the number of small apps that ask you to create an account or user profile, Sign in with Apple was a breath of fresh air. It made signing in easier, and it ensured that you weren’t giving out your real email address when you just wanted to check out an app and see if you actually liked it or not.

It was extremely useful for apps specifically because so many of them required you to set up an account of some kind before you could use them. Furthermore, it was also a considerable boon for developers, who had more users willing to jump on board and try out their apps, rather than simply closing them the first time they were asked to enter an email address.

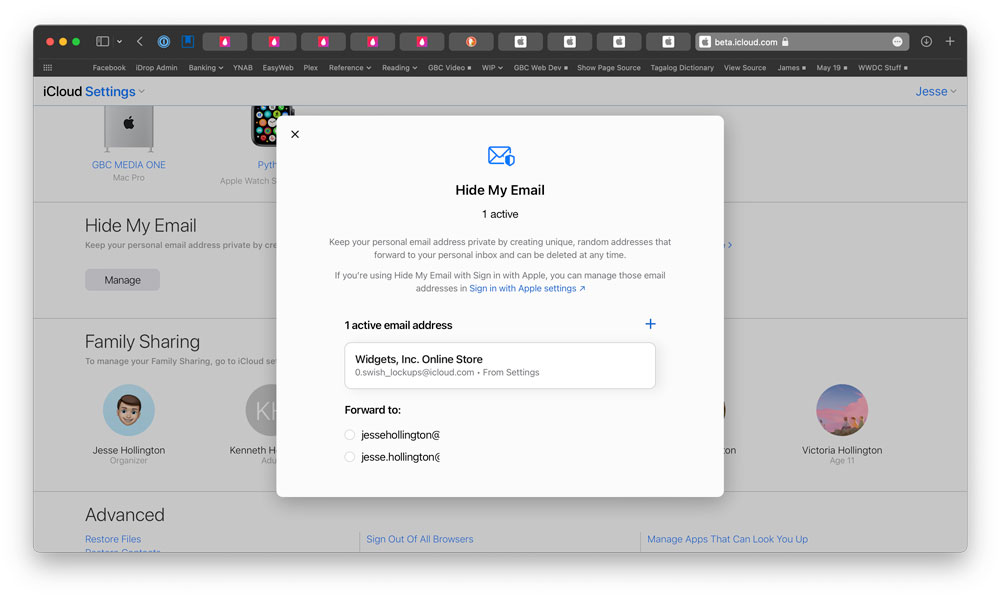

What it does: Hide My Email simply extends this private email address concept, letting you set them up on demand for anything you’d like, rather than only tying them to apps and sites where you sign in with your Apple ID. Here are a few things to know about how Hide My Email works:

- Hide My Email isn’t technically a free service — you must be an iCloud+ subscriber to use it, although that just means that you’re paying at least $0.99/month for 50GB of iCloud storage. Note that the original Sign in with Apple still works without an iCloud+ plan, however.

- Hide My Email uses randomly generated (but still human-readable) email addresses at the @icloud.com domain.

- Even though the temporary addresses use icloud.com, you can actually use Hide My Email with any email provider, as long as your real email address is associated with your Apple ID. You’ll still need to have an iCloud+ account, of course, but you don’t need to be receiving your email at iCloud — you could be using a Gmail account and still benefit from Hide My Email. Messages are simply forwarded from iCloud’s servers to your real email address — wherever that happens to be.

- All of your Hide My Email addresses have to be forwarded to the same primary address. You can’t choose different forwarding destinations on a per-address basis.

- Hide My Email addresses can be created on-the-fly in Safari on your iPhone and iPad, making them easy to fill in. They’ll be associated with a specific website, and you’ll be able to autofill them instead of your real email address when you return to that website.

- You can manage Hide My Email addresses in the iPhone or iPad Settings app, under iCloud, Hide My Email. From here you can create new addresses, choose a different forwarding destination for all of your addresses, deactivate addresses, and even add your own notes to help remember where and why you created them. Addresses created using Sign in with Apple will also be shown here.

- When a message is sent to your Hide My Email address, it will be automatically forwarded to your real address, along with a randomized FROM address that sends your replies through iCloud to continue hiding your address.

When should I use it? Apple’s new Hide My Email is a great feature, but it’s also complex and unnecessary in many cases.

For one thing, unless your email address already contains your full name, you’re not giving up too much privacy by handing it out online. You are, however, voluntarily allowing your “persistent identity” to be used in such a way that the sites and services you enjoy can know a bit more about who you are, and sometimes even reward your customer loyalty.

While Apple makes Hide My Email easy to use within the Apple ecosystem, if you stray beyond Safari you’re going to be stuck either remembering all the addresses you used for different sites, or pulling our your iPhone to look them up.

To be fair, one of the big advantages of Hide My Email is the ability to use a trackable address that can also be discarded when it’s no longer needed. This is naturally great when signing up to questionable sites, or those you don’t plan to return to, such as online stores for one-time orders. It’s not something you should really worry about for more reputable sites where you plan to be a regular customer.

If you’re simply worried about tracking and filtering, there’s actually a feature called Plus Addressing — a much easier solution that works with many major email services, including iCloud and Gmail, and doesn’t require you to remember random email addresses.

Many Gmail users don’t realize that Gmail actually ignores everything after a + sign in the user portion of your email address. This means that emails to “bob+amazon@hollington.ca” and “bob+apple@hollington.ca” both go to the same mailbox at “bob@hollington.ca.”

These addresses still show up in the TO line when you receive those emails, however, so you can see exactly which address they were sent to, and even build filters on them. This plus addressing feature is actually an Internet standard from 2008, so it works in many other email services too, including iCloud, Outlook/Hotmail, and Fastmail.

The beauty of plus addressing is that it just works. You don’t need to set anything up, or configure a new address. Nor do you need to rely on an intermediate mail server to forward your messages. You can fill in an email address on the fly, with anything you like after the + sign, and you’ll get those emails delivered to your inbox.

This can also be very useful if you’re concerned that a site might be selling your email address. For example, if you sign up for an account at “Widgets, Inc.” with “+widgets” in your email address and then suddenly start getting spam emails sent to that address from anywhere else, you’ll know exactly where the spammers got it from — and you can create a rule in your mailbox to throw those messages away.

There are also some more technical downsides to using Hide My Email that you should be aware of:

- If you’re using a non-iCloud email service, messages sent to your Hide My Email address still go through Apple’s iCloud servers. If these are down for any reason, you won’t get those email messages, even if your own mail provider is working fine.

- For the same reason, you’ll get poorer spam filtering on messages sent to Hide My Email. Spam filters on services like Gmail rely on looking up the originating server to help score messages as spam. In the case of Hide My Email, however, all of these inbound messages will be coming from Apple.

- This works the other way too, as messages sent to your Hide My Email address could be more likely to be classified as spam unless you specifically whitelist each one as a “TO” address, which requires additional effort.

To be clear, both of these are limitations of using any email forwarding service, but that’s precisely what Hide My Email is.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that if you’re using another service like Gmail, then Hide My Email isn’t offering as much privacy as you may think. Since all of your “private” email addresses will end up in the same Gmail account, Google will know about every one of them, and be able to tie them all together to your real account. In this case, all you’re really doing is giving Google a big advantage over other advertisers — they may not know who you really are, but Google will know exactly what you’re doing, and it will undoubtedly find a way to make money off this information.

Of course, none of these apply if you’re iCloud Mail anyway, but despite the recent addition of support for custom domains, iCloud Mail is still a weak mail service overall compared to much of the competition, with limited support for things like rules and custom alias addresses. Ironically, even Fastmail provides better push notification support for iOS Mail than Apple’s own iCloud service. It’s definitely not worth switching to iCloud Mail solely to benefit from Hide My Email.

Mail Privacy Protection

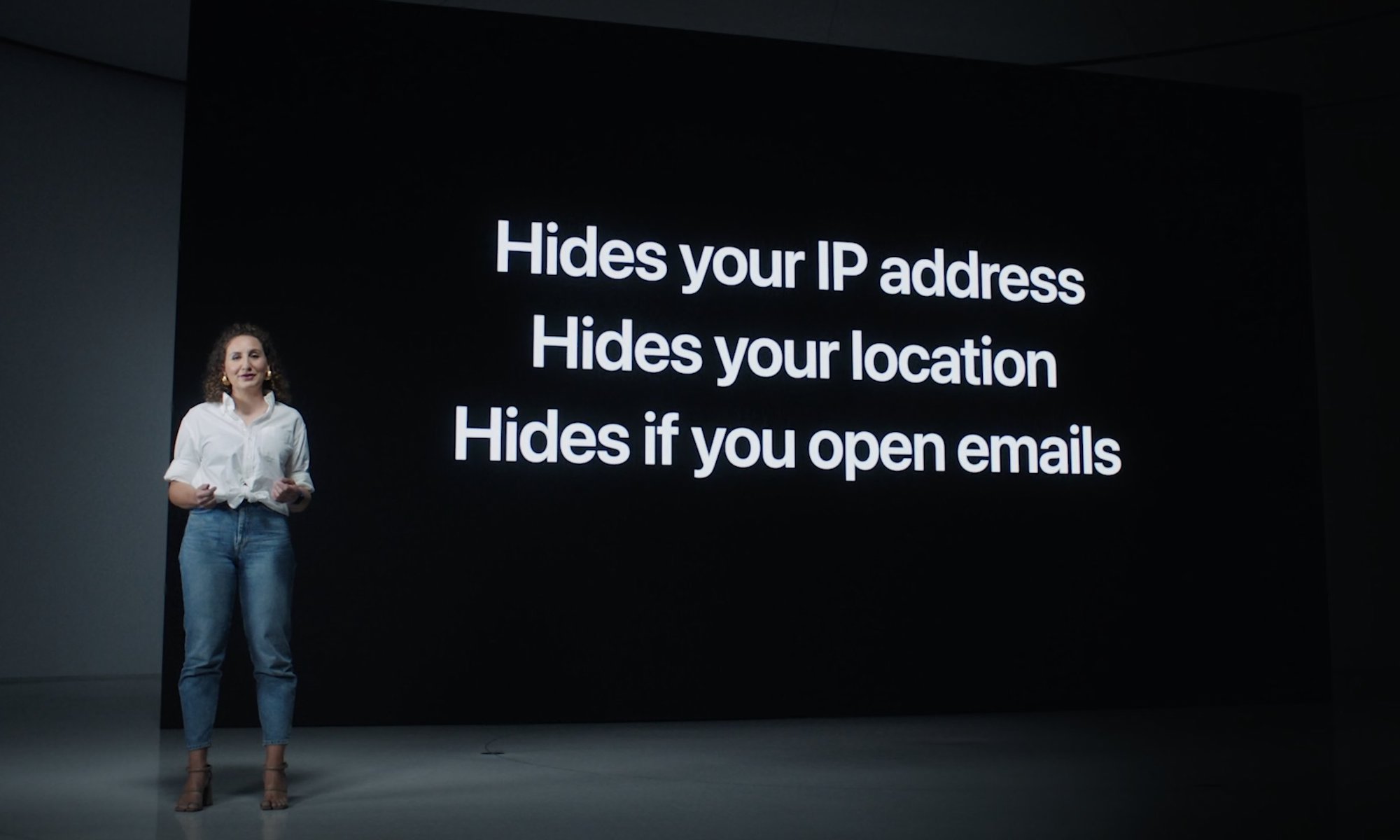

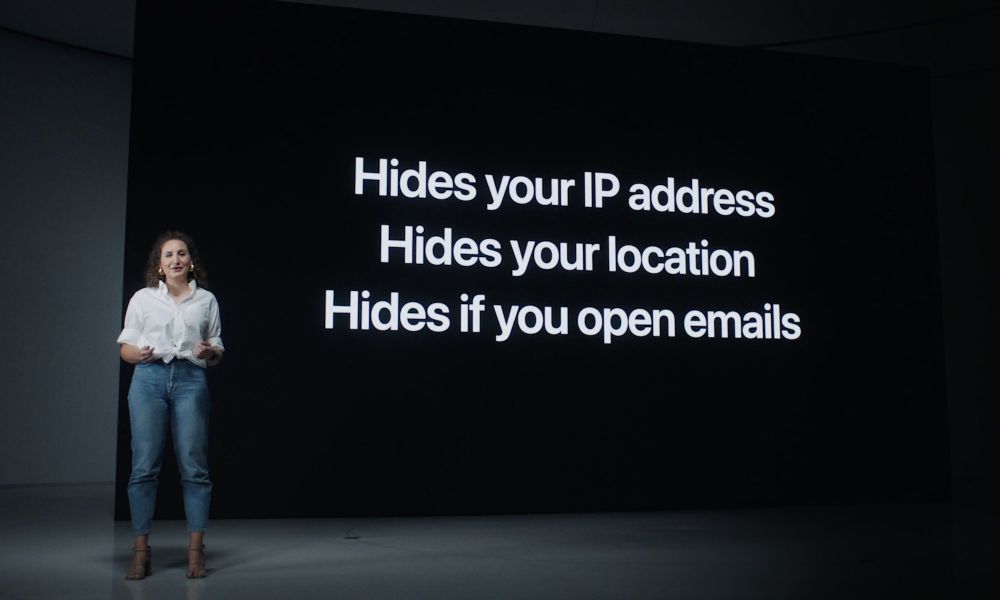

Another new mail-specific privacy feature in iOS 15 is Mail Privacy Protection, and this one is available to all iOS 15 users, whether they subscribe to iCloud+ or not.

What it is: It’s actually a function of the iOS 15 Mail app on your iPhone and iPad, and all that it’s really doing is offering something that many other mail apps and services have already been doing for years.

What it does: Many emails today are basically miniature web pages, and this is especially true of things like newsletters. All the images and much of the other content that are included in these rich emails are actually stored on external servers, and when you open an email newsletter, your email app or service is simply downloading this content directly from those servers.

This allows email newsletter services to track when and how often their emails have been opened, since you’ll be making a connection to their servers in the same way as you would if you opened their site in a web browser. Occasionally, this is done from the actual images themselves, but more often marketing emails include a “tracking pixel” that’s unique to the email that you received.

This means that they can not only track that their emails have been opened, but they can track which accounts are opening their emails, since each recipient gets a different tracking pixel. This also normally gives them your IP address, and allows them to tell if you’ve forwarded the email, since the tracking pixel would go along with it to the next recipient, who would, in turn, open it from a different IP address.

Many other email services and clients have been offering features like this for years. In fact, Gmail introduced it back in 2013, although it only applies if you read your emails through the Gmail web interface, rather than a third-party email client. Apple’s new Mail Privacy Protection just extends these same capabilities to its Mail app.

When Should I Use It? Unfortunately, this is an all-or-nothing choice, and you can’t choose to whitelist specific addresses. If you enable Mail Privacy Protection, it affects everything that comes into your Mail app’s inbox, regardless of which mail service you’re using.

Note that turning this on does mean you’ll be depending on Apple’s servers when reading rich emails, since they’re the ones downloading all the images and feeding them to you. As with Hide My Email, if Apple’s servers are having problems, you’ll find yourself with numerous blank spaces in some of these emails. We observed this several times during the iOS 15 beta cycle, although we’re hoping Apple has fixed this now that iOS 15 has been publicly released.

Also keep in mind that this feature only applies to Apple’s Mail app. It’s completely irrelevant if you’re using a third-party email app.

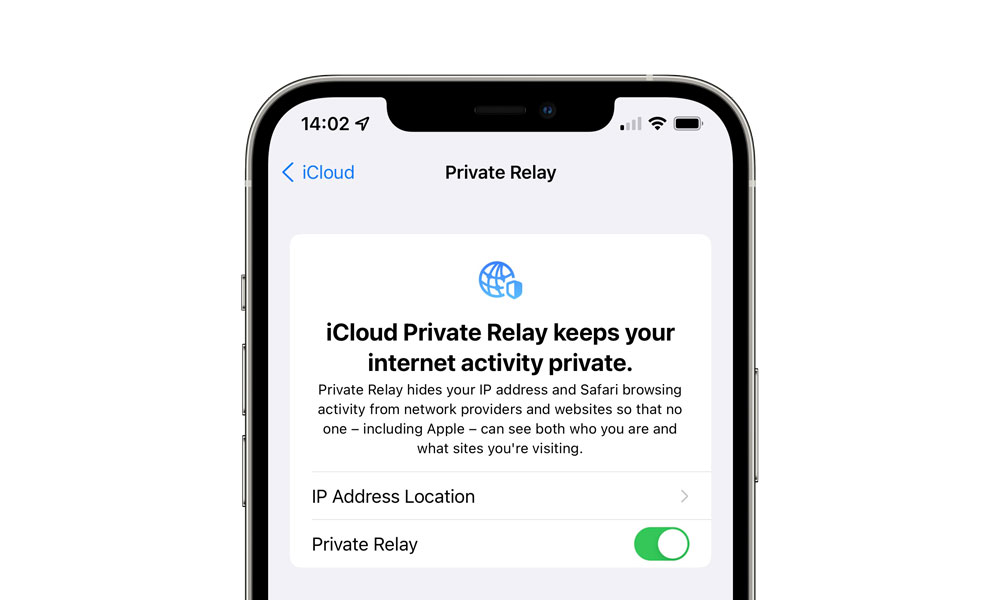

iCloud Private Relay

Last on the list is Apple’s iCloud Private Relay feature, which, although available now in iOS 15, is technically still considered a “beta” feature by Apple.

What it is: iCloud Private Relay is designed to obscure your email address in much the same way that a VPN does, although it goes a step beyond that.

What it does: Apple has cleverly implemented a “double-blind” configuration with iCloud Private Relay, using two independent servers such that no single entity knows both who you are and where you’re going.

Your outbound traffic first goes through a server controlled by Apple, which strips off anything that would specifically identify you, such as your IP address, without decrypting the request to find out where it’s going. Instead, your traffic is forwarded to another server that’s controlled by an outside content provider, such as Cloudflare. That server only knows that the request came from one of Apple’s private relay servers — it doesn’t know your original IP address. It unwraps the request and passes it on to its destination. This process is then repeated in reverse for the returning traffic.

When should I use it? While you’ll need a paid iCloud+ plan to use iCloud Private Relay, it’s a great way to help obscure your real location and identity when browsing the web.

Unless you’re using a VPN service, every website you visit gets to know the IP address that you’re connecting from. This is usually the address of your router, although when you’re using a cellular data connection from your iPhone, it may actually be the specific address assigned to your device.

These addresses rarely change, especially for home networks, making it possible for sites to track your activity over a long period of time, and even share that activity with others. Basically, there’s a good chance that everything coming from the same IP address is coming from the same person, or at least the same family.

Since IP addresses are also assigned by your ISP, it’s often possible to discern your location from your address. This isn’t normally as precise as your exact house or even your street, but in many cases it can expose the neighbourhood you live in, and will almost certainly reveal your city or town.

iCloud Private Relay will obscure this by routing all of your traffic through a generic IP address. You can choose whether that address should reflect your general location and time zone without being too specific, or should simply be somewhere in the same country. Unlike other VPN services, however, Apple isn’t interested in helping you bypass geographic content restrictions.

Like a VPN, iCloud Private Relay also encrypts all of your web surfing traffic on the way to Apple’s servers, so even your ISP can’t tell what you’re doing or where you’re going. This goes beyond the SSL encryption that’s used simply to protect your information in transit, since a VPN encrypts everything, including the addresses of the websites you’re going to.

The service is generally a nice win for privacy, but it’s also not without its downsides, chief among these being that it’s still in beta for now, so you may still encounter performance and stability issues.

It’s also important to keep in mind that this is not a full-fledged VPN service. iCloud Private Relay does not encrypt all of your outbound traffic — it only works in Safari and the built-in browsers in most web apps. Parents should also be wary about enabling this on their kids’ devices, as it will bypass any parental controls on your home router, since it doesn’t get to know where your traffic is going either. If you want to use Private Relay, you’ll need to rely on Apple’s Screen Time features to handle content filtering instead of your home router.

Conclusion

While Apple offers quite a few interesting new privacy features, they are likely pretty complicated to the average user, often require more work than they’re worth, and ultimately affect the sites you enjoy reading.

Internet advertising isn’t as scary as some make it out to be, and newspapers and websites depend on advertising to provide readers with free content. These features can be a jab to content providers who ultimately need data to offer said content.

Chances are, if you’re surfing a website that you’re not comfortable giving your email address to, it’s probably in your best interest to avoid that website in the first place. It’s easier to follow your intuition and stick to websites that you know and trust.