Supreme Court Rules App Store Monopoly Case Can Proceed

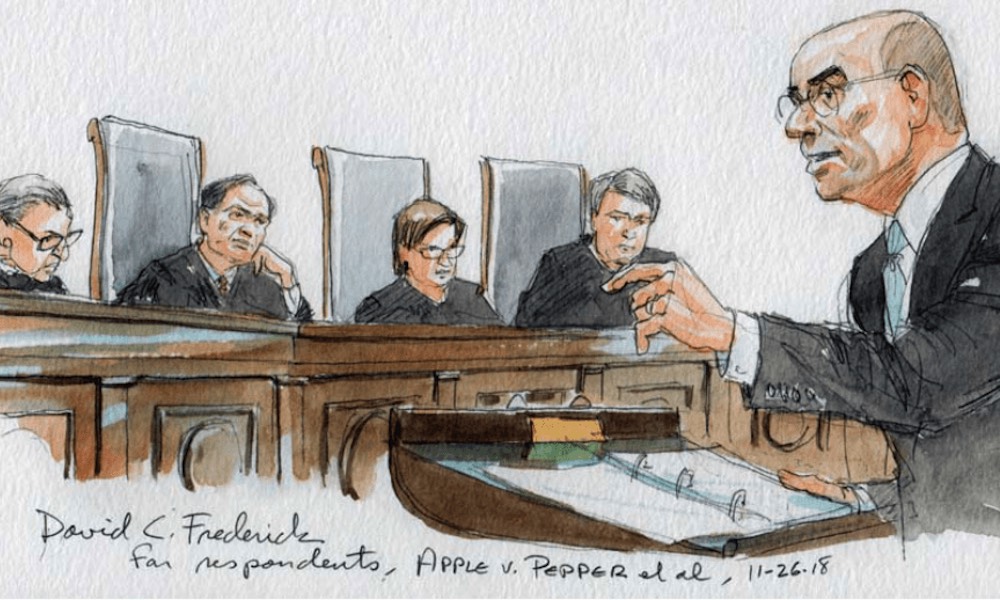

Credit: David C. Frederick via Philip Elmer-DeWitt

Credit: David C. Frederick via Philip Elmer-DeWittToggle Dark Mode

The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that a long-standing antitrust monopoly lawsuit against Apple’s App Store will be allowed to proceed, according to CNBC, paving the way for a potentially landmark decision that could have far-reaching consequences both for Apple itself and the online economy in general.

Background

The original lawsuit was brought against Apple in 2011 by four iPhone owners, accusing the company of maintaining a monopoly on the sale of iPhone apps in order to drive up the prices of apps, which in turn would increase its own 30 percent cut from app sales. The problem was exacerbated by the fact that the App Store was the only marketplace for purchasing apps for Apple’s iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch devices, leaving consumers with no other options, and therefore placing Apple is a monopoly position. Plaintiffs argued that they have “paid more for their iPhones apps than they would have paid in a competitive market,” claiming that the 30 percent commission that Apple takes is “pure profit” for the iPhone maker, who would be pressured to lower this fee in a more competitive environment.

In early 2013, Apple asked for the lawsuit to be dismissed, arguing that it can’t be considered a monopoly because it has no role in setting prices for apps, and the 30 percent cut is simply a “distribution fee” which doesn’t violate antitrust laws. Although the lawsuit was dismissed later that same year, it wasn’t solely in recognition of Apple’s arguments, but rather due to the fact that the plaintiffs couldn’t claim that they had “personally suffered an injury-in-fact based on Apple’s alleged conduct” because they hadn’t actually purchased any of the apps in question.

That ruling didn’t preclude the case being refiled, however, and it was resurrected in early 2017 when the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the plaintiffs could sue Apple directly, despite the iPhone maker’s arguments that the App Store was simply a storefront, simply because that was the only place where the apps could be purchased from, and that the plaintiffs allegations that Apple exercises monopoly power to force iPhone owners to pay Apple higher-than competitive price for apps were valid enough to warrant further exploration.

Apple appealed the lower court decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, which agreed last June to hear the case, with the case landing before the court later in the year.

In its argument against allowing the lawsuit to proceed, Apple cited a 1977 Supreme Court ruling, Illinois Brick, as precedent, which limited damages for anti-competitive conduct to those who overcharged directly, rather than those who simply paid an overcharge passed on by others. In essence, Apple argued that it was simply acting as an agent for a wide array of independent app developers, who are free to set the actual prices that Apple passes on through its storefront. Apple also made the argument that siding with the plaintiffs could “threaten the burgeoning field of e-commerce, which generates hundreds of billions of dollars annually in U.S. retail sales,” and would affect not only Apple, but companies such as ticket site StubHub, Amazon’s Marketplace, and eBay.

In countering this argument, lawyers for the plaintiff argued that Apple’s 30 percent cut forces developers to charge higher prices than they otherwise would, thereby passing Apple’s costs directly on to the consumers as well, since developers have no choice but to purchase their apps through the App Store. The plaintiff’s lawyers suggest that a more competitive landscape is needed to give developers the freedom to set lower prices on other app stores, and also argued that service providers such as Apple and Uber need to be held accountable for their involvement in driving prices up by forcing those selling through their services to charge higher prices to account for the necessary costs of doing business through them.

Today’s Supreme Court Ruling

Today’s 5-4 ruling by the Supreme Court rejected Apple’s claims that end users could not bring a lawsuit against the company due to its role as a storefront, paving the way for the class-action case against Apple to proceed through the courts without any further possible challenges to its legitimacy.

Apple’s line-drawing does not make a lot of sense, other than as a way to gerrymander Apple out of this and similar lawsuits.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh

In the Court’s opinion, Justice Brett Kavanaugh ruled that iPhone owners are in fact “direct purchasers from Apple” and therefore have a legal standing to sue Apple for antitrust violations. Justice Kavanaugh rejected Apple’s assertions that users had no basis for the lawsuit due to it being the developers who set the prices for their own apps, stating that the original 1977 precedent cited by Apple, Illinois Brick, wasn’t about who set the price but rather about who the end consumer had the direct purchasing relationship with.

Justice Kavanaugh adds that in almost any retail setting, prices are at least partially set by the manufacturer or supplier of the original products, however the purchasing relationship is still between the customer and the retailer, and it shouldn’t matter whether the retailer (e.g. App Store) pays the original manufacturer (e.g. developer) and later adds a markup, or whether they simply take a commission before passing the remaining payment on.

Dissenting Opinion

In a strongly-worded dissenting opinion joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, Justice Neil Gorsuch agreed with Apple’s contention that it is the developers, and not the users, who are the only ones with legal standing to sue Apple, since they are the injured party, and they alone control the actual prices of their apps.

Plaintiffs can be injured only if the developers are able and choose to pass on the overcharge to them in the form of higher app prices that the developers alone control.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch

Justice Gorsuch noted that the “plaintiffs admitted as much in the district court” when lawyers implied that developers would increase their prices to cover Apple’s “demanded profit.” The dissenting opinion also cites the 1977 case upon which Apple’s challenge was based, Illinois Brick, noting that the position taken by the plaintiffs that Apple could be held responsible for App Store pricing would “necessitate a complex inquiry” into exactly how pricing decisions by independent developers are actually impacted by Apple’s conduct, as opposed to many other “relevant market variables,” as well as opening a can of worms about how damages should be apportioned between app developers and their customers should Apple be determined to be at fault.

In other words, developers could also make a claim to recover the 30 percent that they paid to Apple, in which case they would be “seeking a piece of the same 30% pie” that could already have been awarded to customers.

Will the court hear testimony to determine the market power of each app developer, how each set its prices, and what it might have charged consumers for apps if Apple’s commission had been lower? Will the court also consider expert testimony analyzing how market factors might have influenced developers’ capacity and willingness to pass on Apple’s alleged monopoly overcharge? And will the court then somehow extrapolate its findings to all of the tens of thousands of developers who sold apps throughthe App Store at different prices and times over the course of years?

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch

Justice Gorsuch also goes on to note that this is complicated even further due to Apple’s tiered pricing structure. Since in most cases developers can’t raise their prices by exactly enough to cover Apple’s 30% cut, this leaves them with the more difficult choice of simply absorbing Apple’s share as a cost of doing business, or raising their price even higher and risking an impact to sales, while also gaining more profit for themselves. With this pricing model, Justice Gorsuch notes, it’s difficult for plaintiffs to make their case that Apple’s 30 percent commission is the only thing driving their pricing decisions, and not simply one of many expenses that simply factor into a developer’s normal cost of doing business.

Another interesting point that Justice Gorsuch’s dissenting opinion makes is that Apple would apparently be able to evade the Court’s test, which hinges on how money is being exchanged, by amending its contracts to pay 100% of the price of an app to the developers, and then requiring them to pay 30% back to Apple, rather than simply taking the 30% off the top. “This exalts form over substance,” Justice Gorsuch notes, and “will only induce firms to abandon their preferred — and presumably more efficient — distribution arrangements in favor of less efficient ones, all so they might avoid an arbitrary legal rule.”

It’s important to note, however, that the U.S. Supreme Court ruling only gives the green light for the class-action case against Apple to proceed. The Court is ruling on the legal standing for the case — whether it’s even possible to make the challenge in the first place — but it will be up to the lower courts who hear the actual lawsuit to decide whether the plaintiff’s actual claims have any merit.

To be sure, if the monopolistic retailer’s conduct has not caused the consumer to pay a higher-than-competitive price, then the plaintiff ’s damages will be zero.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh

As Justice Kavanaugh noted in the Court’s opinion, it’s entirely possible that the courts could ultimately determine that Apple’s conduct had absolutely no impact on app pricing — that app developers would set higher prices anyway — but the Supreme Court has clearly decided that it’s up to the lower courts to determine this. However, if the opinions provided in today’s Supreme Court decision are any indication, it seems likely that this case will continue to be tied up in legal wrangling for many more years to come.

The full Supreme Court ruling, originally posted by CNBC, can be read below.

Apple Supreme Court ruling by on Scribd