Supreme Court Weighs in on Controversial Apple App Store Monopoly Case

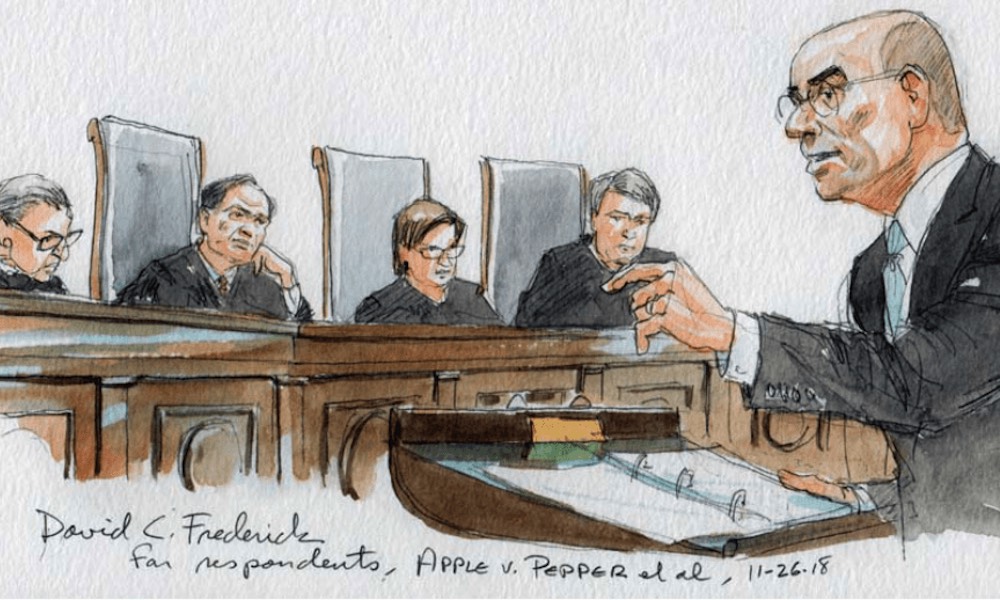

Credit: David C. Frederick via Philip Elmer-DeWitt

Credit: David C. Frederick via Philip Elmer-DeWittToggle Dark Mode

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) this week began hearing oral arguments in the controversial case of Apple v. Pepper — a contentious class-action lawsuit which accuses Apple not only of “holding and maintaining a monopoly” on app distribution, but also overcharging consumers for App Store purchases.

Apple v. Pepper is a unique case with potentially damaging and universal implications — not only for Apple and the future of its thriving App Store, but likewise for tech companies including Google, Microsoft, Facebook and others, as well.

In essence, the case is seeking to determine WHO buyers are entering into a transaction with when they go to purchase and download an app from the App Store using their iPhone or iPad.

If the courts decide they’re purchasing the app from Apple, vis á vis the iOS developers who built and maintain the title, then Apple, itself, could potentially be accused of antitrust behavior and face up to millions of dollars in penalties.

The case, which could reportedly take the SCOTUS judges several months to issue a ruling on, was originally filed back in 2011, with both Apple and AT&T (America’s exclusive iPhone distributor, up until that time) named as plaintiffs.

While accusations against AT&T were dropped, it wasn’t until a January 2017 ruling by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals which ultimately paved the way for Apple v. Pepper to be heard — and accepted or rejected — by the highest court in the land.

SCOTUS judges won’t be handing down an official ruling in this case. However, their decision of whether or not the case should continue still has far-reaching implications.

Apple’s First Arguments

In the first four-hour session of oral arguments on Monday, Apple lawyer Daniel Wall pointed to a ruling in the 1977 landmark case of Illinois v. Illinois Brick Co., which determined that only the direct purchaser can file antitrust accusations in a court of law.

As Apple Insider points out: in that 1977 ruling, “the court feared there would be far-reaching and complex circumstances with a serious risk of multiple liability for defendants,” which, in Cupertino’s case, translates to the feasibility of Apple (and its app developers potentially being sued over the same purchase.

Developers, according to Wall, are in that scenario Apple’s direct customers, since they are the ones “buying a package of services which include distribution and software and intellectual property and testing” via their 30 percent commission.

But since this commission is agreed upon between Apple and its developers beforehand (thus, allowing them to set the price of their app bearing the 30 percent charge in mind), Wall argues that app pricing is ultimately at the developer’s wishes, and is not imposed or otherwise obfuscated by Apple, itself.

SCOTUS Shoots Back

After hearing the first round of arguments, the SCOTUS judges appeared to push back on some of Apple’s biggest claims, with Justice Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor all “questioning the logic” behind Apple’s arguments.

“From my perspective, I’ve just engaged in a one-step transaction with Apple,” Justice Kagan said, noting that every stage of a consumer’s purchase is routed directly through Apple’s App Store.

Kagan went as far as to suggest that the ruling in Illinois v. Illinois Brick Co. — which involved a concrete producer selling their products, which were previously used in construction for their own customers, to other independent contractors — may not even apply in this case, and Justice Breyer further noting that the small scope of Illinois v. Illinois Brick Co. meant the case wasn’t impacted by complex antitrust matters, as is the case, in this case.

Justices Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch, meanwhile, appeared to suggest that a thorough re-examination of the Illinois Brick Co. ruling might be necessary, with Alito specifically pointing to the “tens of thousands” of app developers who HAVE NOT filed similar lawsuits against Apple. Gorsuch, who’s now in his Sophomore year of hearing cases on the court, suggested even further the possibility of overruling the Illinois Brick Co. verdict, citing how some states currently allow indirect purchasers to file lawsuits, already.

Worth reiterating one last time is that while they’re weighing in on the overall arguments presented by both sides, the SCOTUS Justices are NOT handing down an official ruling in this case. Rather, they’re asking questions designed to delve further into the truth, and, ultimately, forge a conclusion on whether they believe the case will stand or fall when it’s sent back to the lower courts sometime in 2019.

To read more about the case of Apple v. Pepper, be sure to check out all the updates and official court documents published to the official SCOTUS Blog.