Tile Provides Location Data to Law Enforcement (What About AirTags?) [Update: Tile Responds]

Tile

Tile

Toggle Dark Mode

Update: Following the publication of this article, a spokesperson from Life360, Tile’s parent company, reached out to us to provide further clarification. See below for their response.

If you’ve been using a Tile tag, you may not be the only one watching its location. In a revealing new report, the company behind the eponymous tracking tags has also been handing over location data on its users to law enforcement officials.

In a new scoop, 404 Media reports that a hacker was able to break into Tile’s systems and not only steal significant amounts of customer data but also gain access to internal tools that showed the company is set up to process location data requests for law enforcement, revealing the whereabouts and movements of any Tile customers that police and other law enforcement officials choose to target.

Although the block of stolen data didn’t include any specific user location information, it shone a light on the privacy dangers of such trackers—both because hackers were able to breach the system and because the company could cooperate with law enforcement requests.

[This] is still a significant breach that shows how tools intended for internal use by company workers can be accessed and then leveraged by hackers to collect sensitive data en masse. It also shows that this type of company, one which tracks peoples’ locations, can become a target for hackers.Joseph Cox, 404 Media

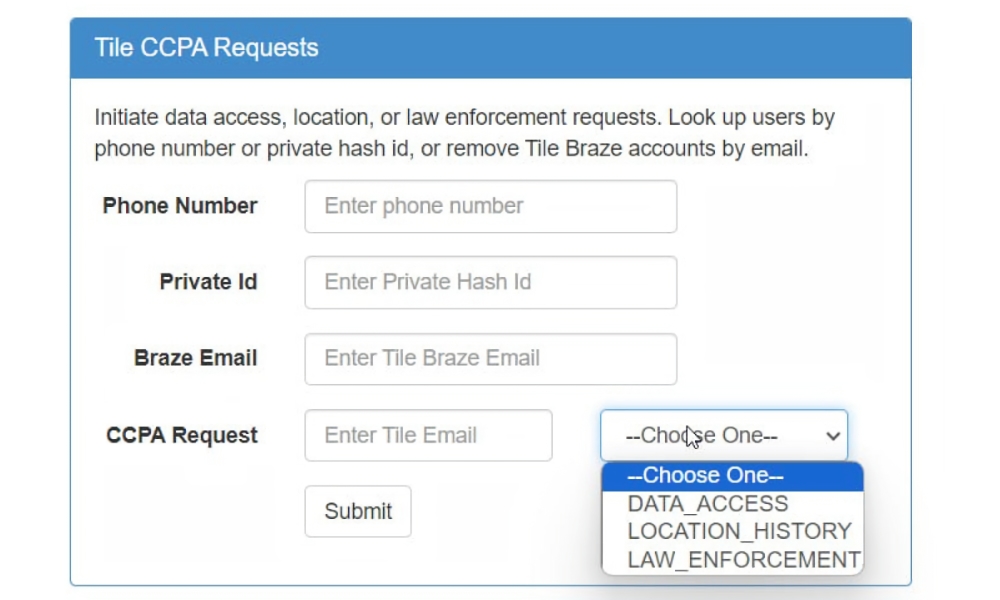

The hacker told 404 Media that they had obtained credentials for a system that “they believe belonged to a former Tile employee,” with one tool specifically designed to “initiate data access, location, or law enforcement requests.” The tool can be used to look up Tile customers based on their phone number or at least one other identifier. A drop-down menu allows the operator to select one of three request types: “DATA_ACCESS, LOCATION_HISTORY, or LAW _ENFORCEMENT.”

Another system the hacker breached contained customer data, including names, addresses, phone numbers, and order and payment information. 404 Media was provided with a sample of the data and independently confirmed its legitimacy by using a random sampling of email addresses and either trying to sign up for accounts on Tile’s website or contacting people directly to verify that the information in the data dump belonged to them.

In a statement to 404 Media, Tile confirmed that “an extortionist contacted us, claiming to have used compromised Tile admin credentials to access a Tile system and customer data.” The spokesperson emphasized that this was a customer support platform containing “limited customer information,” not the core Tile service platform, which contains considerably more sensitive information such as credit card numbers and passwords. After404 Media contacted Tile and proved the stolen data was accurate, Tile also posted a statement on its website.

However, Tile evaded the question of whether the hacker had the required access that would have allowed them to perform a location data request. The company also didn’t comment on how it handles law enforcement requests.

Update: Tile Responds

Following the publication of this article, a representative for Tile’s parent company, Life360, reached out to us with the following comment:

The support platform is not “intended for law enforcement” nor does it provide location data to law enforcement. The tool in question is part of a multi-phased process for initiating law enforcement data requests. What is seen in the excerpted screenshot from 404 Media and the Verge is a single step for Life360 personnel to initiate a request to respond to a law enforcement request for Tile user data. That step does not access or share Tile user data. Life360 maintains multiple layers of automated and human intervention prior to responding to a law enforcement request for Tile user data. We have also challenged the legal sufficiency of warrants where appropriate.Life360 spokesperson

What About AirTags?

An incident like this should raise concerns about how any kind of item tracking tag you own could be subverted to track you without your consent. However, while no system is immune to such things, the good news is that Apple’s AirTags present considerably fewer risks due to the way that Apple handles your information.

To be clear, nobody should argue that Tile shouldn’t cooperate with law enforcement when it receives a lawful request for information. It’s less clear what Tile’s standards are for handling such requests, but we’re hoping that they require a proper warrant and aren’t just willing to respond to off-the-cuff requests by individual investigators (update: see the comments from Life360 above)

Even Apple is required to comply in a scenario like this — and the company does so willingly when a proper warrant is received for customer information. However, Apple can’t give law enforcement officials what it doesn’t have — and that includes the location of your AirTags.

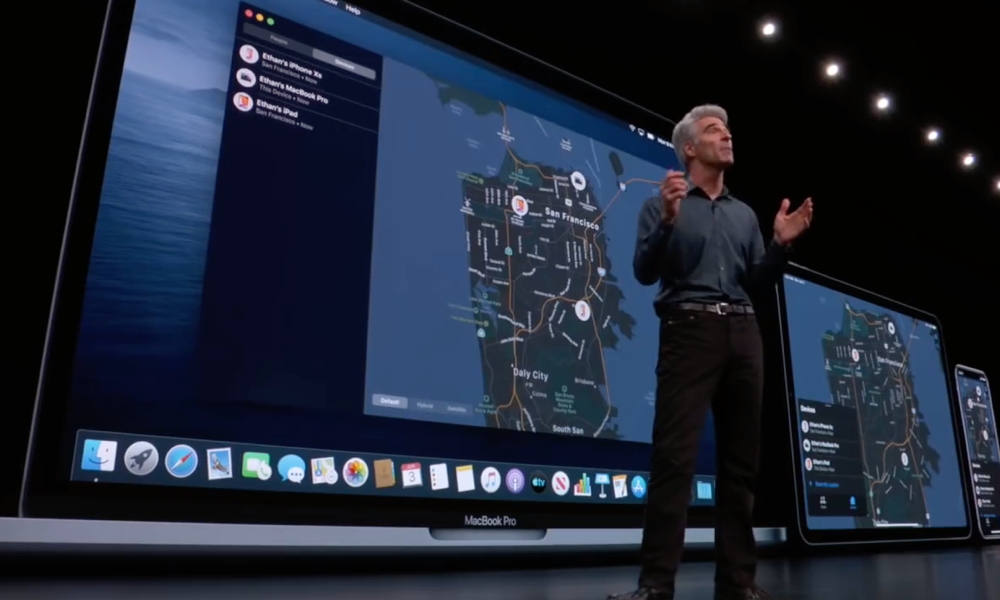

Apple knew from the start that creating a network that could track powered-off iPhones and portable tags could be a privacy nightmare of Orwellian proportions. So, it set out to ensure that a device’s owner would be the only person who could ever track that device. Years before Apple announced AirTags, it built an incredibly clever encryption system that was so sophisticated that even Apple itself couldn’t track your devices.

In fact, the system is so clever that Apple can’t find the location of AirTags at all – even in broad terms without a name attached. When an AirTag’s location gets reported by a random iPhone, the device picking it up encrypts its location using a public key that the AirTag supplies. Only the owner has the private key required to decrypt that data, stored in the Find My app on their iPhone, iPad, or Mac. So, what goes to Apple’s servers is an unintelligible blob of data.

It sits there, undecipherable by anyone without the proper key. When the AirTag’s owner looks for their AirTag, their iPhone requests that blob, using a cryptographic hash to identify it, then downloads it and decrypts it on the owner’s device using the locally stored private key. This all happens entirely in the background, in seconds, but there’s a lot of computing and math going on under the hood to make sure your location and the location of your AirTags stay private.

It’s a move that’s typical of Apple. The company is frequently underestimated for the brilliance of its engineers who come up with these techniques. Strong encryption and data anonymization have been Apple’s bulwark against privacy-invasive requests for years. We saw it with the infamous FBI case in 2016, and it routinely comes up every few years as forensic experts accuse Apple of being “jerks” and lawmakers chide Apple for making the iPhone a “safe haven for criminals.”

Thankfully, none of this has deterred Apple from tightening its security. As lawmakers have threatened to outlaw end-to-end encryption, Apple has doubled down to make your iPhone and the data you store in iCloud even more secure.

In 2021, Apple tried to throw a bone to regulators with a controversial plan to scan iCloud Photos for child abuse images (CSAM). When it abandoned that plan after a public backlash, Apple shrugged and enabled nearly full end-to-end encryption anyway (it’s enough to make us wonder if the CSAM scanning was essentially a bluff so Apple could say it tried to appease law enforcement).

It’s not that Apple doesn’t want to help catch criminals, but rather that the company recognizes that such tools are a double-edged sword. Anything that can be used to invade the privacy of a criminal can also be used to invade your privacy. That’s a Pandora’s box that Apple refuses to open, which is why Apple CEO Tim Cook described a “backdoor” into the iPhone as “the software equivalent of cancer” and “not something that should be created.”

Many lawmakers are seemingly naive enough to believe that Apple could create a backdoor into its encryption that would never be used by anybody but “the good guys,” but history has shown that once a tool exists, it can easily fall into the wrong hands. This has even happened with tools created by the US National Security Agency, which we’d hope safeguards its tools much better than a local county forensics lab.

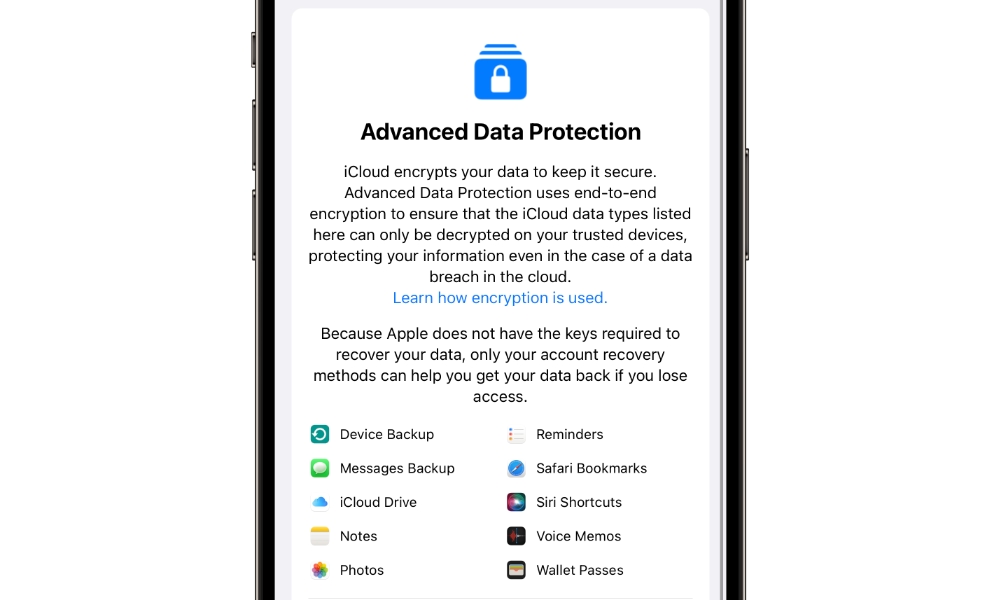

Meanwhile, Apple continues to tighten its privacy and security even more to create a nearly “zero knowledge” system for your personal data. In the unlikely event that a hacker breaks into Apple’s systems, there’s almost nothing they can find out about you, and while Apple will still eagerly comply with law enforcement requests, if you have Advanced Data Protection turned on, most of what it can hand over will a useless blob of encrypted data. This includes everything from your iCloud Photos and Notes to your iCloud Backups. Only Mail, Calendars, and Contacts are excluded because of the need for these technologies to work with industry-standard protocols that don’t support end-to-end encryption.