North Dakota Changes Course as More States Launch Apple-Google COVID-19 Apps

Credit: Jesse Hollington

Credit: Jesse Hollington

Toggle Dark Mode

Following the launch of the first COVID-19 exposure notification app in the U.S. last week in Virginia, three more U.S. states have gotten on board in releasing their own apps, further expanding the coverage of the privacy-focused contact tracing approach within the U.S.

While several European countries had ENS apps out back in June, the deployment of the technology in North America has been considerably slower.

Canada was actually the first to roll out an ENS app on this continent, after announcing its intention to work with Apple and Google to do so back in June, but the most part U.S. states were considerably more silent on the matter, with only four announcing that they had signed on as of mid-July — Virginia, Oklahoma, Alabama, and South Carolina.

So it’s not necessarily all that surprising that Virginia was the first one to actually release a COVID-19 ENS app last week, nor should it be a shocker that Alabama has also joined the ranks of states with apps using the Apple-Google API. However, more interesting among the new entries is North Dakota, which had previously stated that it would be going its own way in developing a contact tracing app that was based on its own technology.

To be clear, North Dakota originally said it was going to use the Apple-Google exposure notification system, but later decided that it was going to instead join South Dakota, Wyoming, Rhode Island, and Utah in developing a Care19 contact tracing app that would use a centralized GPS location database that was somewhat controversially tied in with Foursquare and Google in order to process location data (despite claims that data wasn’t being shared with any third parties).

However, it seems that both North Dakota and Wyoming at least have had a change of heart, with the Care19 app that’s now available on the App Store clearly using the Apple and Google system, rather than whatever homebaked solution the states had originally come up with. This suggests that the other states in the group — South Dakota, Rhode Island, and Utah — while soon follow suit as well.

According to North Dakota Governor Doug Burgum, the state was the first to launch a contact tracing app in the U.S., although it was actually beat out by the Canadian province of Alberta for the first contact tracing app in North America. However, neither of these initial attempts used the Apple-Google exposure notification API.

More significantly, however, North Dakota’s Care19 is also the first COVID-19 ENS app that will be tying into the National Key Server — presumably referring to the one being set up by the Association of Public Health Laboratories — which will allow exposure notifications to work across state lines. This is something that’s crucially important in the U.S. where each state is developing its own app, unlike the national approach being taken by Canada and most European countries, since international travel is still largely banned, but interstate travel isn’t nearly as restrictive.

While North Dakota’s Care19 app is already available on both the App Store and Google Play Store, Wyoming’s is expected to launch later today, while Alabama’s will be available early next week.

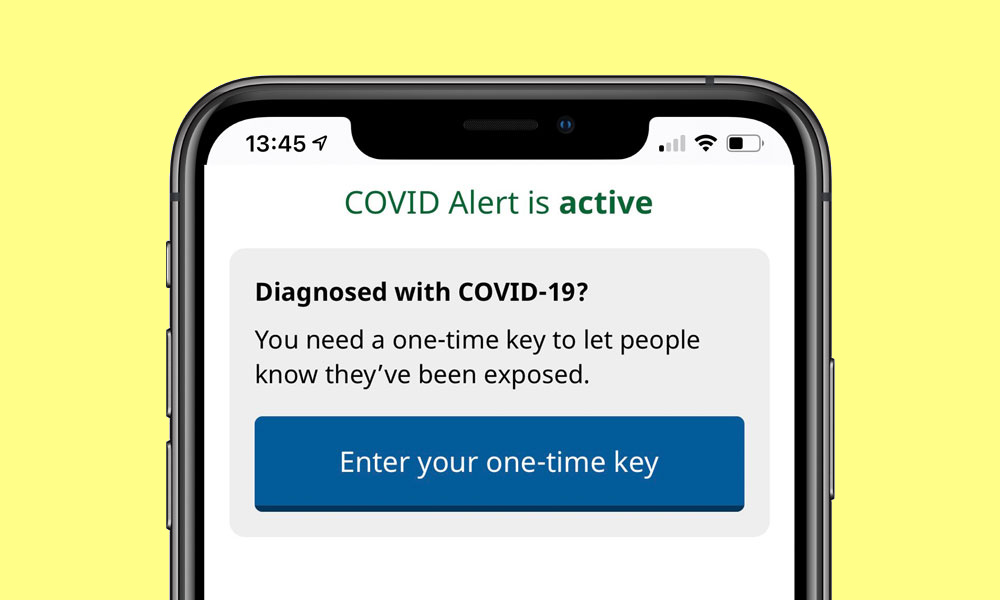

As with all other apps that use the Apple-Google Exposure Notification System, the apps are heavily focused on privacy, as they’re restricted from using any location services technologies at all, nor are they permitted to collect any more personal information than is absolutely necessary.

Instead, they use Bluetooth technology to exchange randomized and anonymous identifiers with other iPhones and Android phones that come within a certain range for more than a few minutes. All of these collected IDs are stored only on each user’s smartphone, and are never transmitted to the cloud. When a user received a positive diagnosis for COVID-19, health officials provide them with a PIN that can be used to optionally report that diagnosis to the system, in which case their own anonymous ID (and only that one ID) is uploaded to a centralized server. Other smartphones poll this server on a regular basis to see if there’s a match with one of the IDs they’ve already stored, and if so, the user is alerted that they may have came into contact with somebody who was diagnosed with COVID-19.