The UK Still Wants Access to iCloud Data — Just Not as Much

Oskar M?odzi?ski

Oskar M?odzi?ski

Toggle Dark Mode

The iCloud snooping saga in the UK isn’t over. Despite a mid-August report that the UK Home Office was backing down on its demands for access to all iCloud user data in the face of pressure from the United States, it now appears the UK government has only made a partial retreat.

Earlier this year, The Washington Post blew the whistle on a secret order by the UK government that would require Apple to provide its intelligence services with full access to iCloud user data — including encrypted data.

What made this particularly egregious, aside from its draconian cloak of secrecy, was that the request wasn’t limited to British citizens. As incredible as it sounds, UK officials wanted Apple to hand over the keys to unlock all encrypted iCloud data, for all users, in every country.

Apple naturally fought back against these demands. However, because UK law includes criminal penalties for anyone who even admits receiving one of these secret orders — innocuously named Technical Capability Notices (TCNs) — Apple had to fight this in a secret court. Fortunately, insiders have been willing to leak details to outlets like The Washington Post and the UK’s Financial Times, both of which have continued to shine a light on the unfolding drama.

The Standoff Moves to a Smaller Playing Field

It should come as no surprise that officials in the US government were less than impressed with the UK’s attempts to effectively spy on US citizens. Lawmakers urged the US intelligence chief to push back against the UK, warning that it could undermine existing intelligence agreements between the two countries.

The US Congress also sent a bipartisan letter to the UK’s Investigatory Powers Tribunal, insisting that the “cloak of secrecy” around TCNs be removed entirely. “Secret court hearings featuring intelligence agencies and a handful of individuals approved by them do not enable robust challenges on highly technical matters,” they wrote.

By midsummer, we saw the first signs that the UK might blink in the face of US pressure. In August, US Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard and the Financial Times both reported that the UK was indeed backing off.

“The UK has agreed to drop its mandate for Apple to provide a ‘back door’ that would have enabled access to the protected encrypted data of American citizens and encroached on our civil liberties,” Gabbard said in a tweet. The Financial Times echoed the DNI’s statement and added that its own sources described the issue as “settled,” claiming the UK had “caved” to US pressure.

Sadly, those hopes proved to be premature. Later that month, the Times reported on new court filings by the UK’s Investigatory Powers Tribunal that suggested that the train was still rolling down the tracks, while at the same time showing just how insidious and far-reaching the UK government’s request was.

It seems we should have paid closer attention to the fine print in Gabbard’s statement: “The UK has agreed to drop its mandate for Apple to provide a ‘back door’ that would have enabled access to the protected encrypted data of American citizens…” (emphasis added). It turns out the UK isn’t backing down from its demands for backdoor access to iCloud user data — it’s merely narrowing the scope.

According to the Financial Times, the UK Home Office has now issued a new TCN to Apple, demanding the same level of backdoor access into iCloud, but now limiting it to data belonging to British users.

The UK Home Office demanded in early September that Apple create a means to allow officials access to encrypted cloud backups, but stipulated that the order applied only to British citizens’ data, according to people briefed on the matter.

Anna Gross and Tim Bradshaw, Financial Times

The Home Office presumably hopes that narrower demand will provoke less of a backlash from Washington. While it’s doubtful that the US will be pleased about this, it now has far less leverage since the order no longer directly affects US interests.

Nevertheless, the reduced scope doesn’t actually narrow the privacy implications. While UK spooks may be limited to snooping on data belonging to British citizens or other UK residents, the very act of creating a back door into any end-to-end encryption system creates a massive privacy risk to the entire system.

“If Apple breaks end-to-end encryption for the UK, it breaks it for everyone,” Caroline Wilson Palow, legal director of Privacy International, told the Times. “The resulting vulnerability can be exploited by hostile states, criminals and other bad actors the world over.”

Apple remains under a gag order that prevents it from discussing any of this. Still, if he were allowed to speak on it, I can only imagine Tim Cook would say something along the lines of his 2016 response to the FBI’s request for a similar backdoor, which he called the ”software equivalent of cancer.”

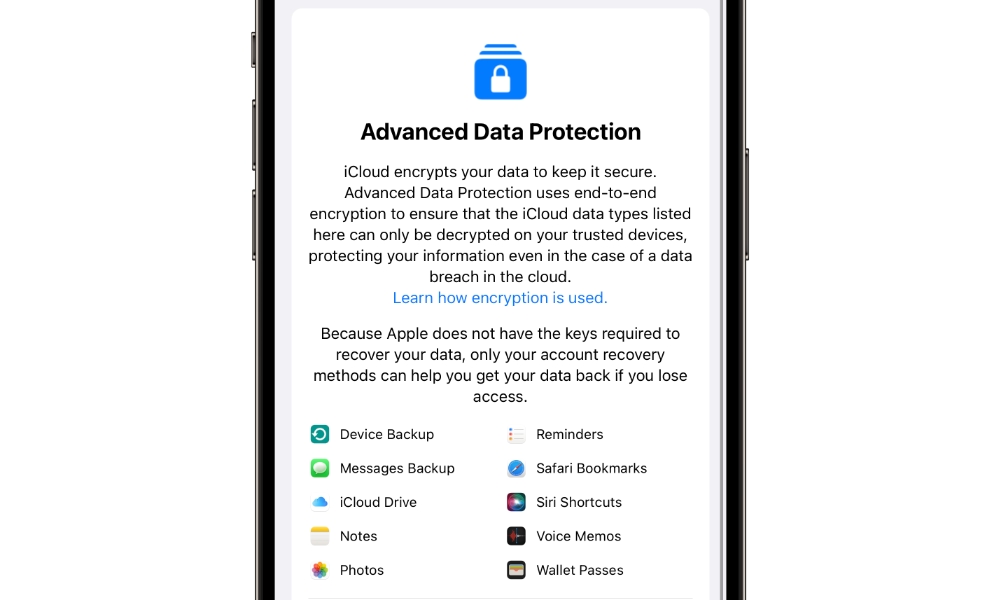

This is a Pandora’s Box that Apple has repeatedly refused to open, and it will undoubtedly continue to fight the UK’s demands. In the meantime, it’s taken steps to remove any false sense of security that iCloud users may have in the UK. Earlier this year, it turned off Advanced Data Protection in the UK, preventing users in that country from accessing its full end-to-end encryption features.

Apple never explained why it did this — again, it’s not allowed to even admit to receiving a TCN from the UK government, much less talk about what it’s being asked to do — but most experts believe that it’s to avoid being forced to create a back door into its most secure iCloud encryption. From all the reports we’ve seen so far, the UK demands are primarily focused on gaining access to iCloud user data, and are not particularly concerned with the means and methods. Disabling Advanced Data Protection allows Apple to comply with the order by providing data that’s not end-to-end encrypted in the first place.

Apple issued a more oblique statement to the Financial Times today, referring only to the “rise of data breaches and other threats to customer privacy,” while omitting any mention that the biggest threat to customer privacy for UK citizens may very well be their own government.

Apple is still unable to offer Advanced Data Protection in the United Kingdom to new users. We are gravely disappointed that the protections provided by ADP are not available to our customers in the UK given the continuing rise of data breaches and other threats to customer privacy.

Even without Advanced Data Protection, there’s still plenty of data in iCloud that’s been fully end-to-end encrypted for years, including passwords and other keychain data, payment information, health data, Messages in iCloud, journals data, home data, pins, saved locations, and search history in Apple Maps, history, tab groups, and iCloud tabs in Safari, personalization and settings in Siri, the learned vocabulary for things like autocorrect and other keyboard functions, and even Memoji and unpublished invitations in Apple Invites.

The documents seen by the Financial Times in August reveal that the UK Home Office wants all of this — every piece of data stored in iCloud — as it claims it’s the only way to combat terrorism and child sexual abuse. Security experts and privacy experts strongly disagree, as does Apple.

“As we have said many times before, we have never built a back door or master key to any of our products or services, and we never will,” Apple reiterated in its statement.

The only question now is how far the standoff will escalate. In 2023, Apple threatened to pull iMessage and FaceTime from the UK entirely if the government proceeded with a controversial surveillance bill, which critics called a “snooper’s charter” — and others like WhatsApp and Signal vowed to follow suit. Faced with the prospect of depriving their citizens of major messaging platforms, UK officials backed off, claiming the technology didn’t exist to do it properly and safely. That may have been a face-saving gesture on the government’s part, but we’ll have to wait and see if the Home Office comes up with a similar way to extricate itself from what is sure to become a losing standoff for British citizens.