No, Apple Is Not Selling Your Siri Recordings to Advertisers

Credit: Miguel Tomás / Unsplash

Credit: Miguel Tomás / Unsplash

Toggle Dark Mode

Last week, Apple agreed to pay $95 million to settle a five-year-old Siri eavesdropping lawsuit. As with most such settlements, the company has made it clear that the payout is not an admission of any guilt or culpability.

In fact, in the settlement proposal, Apple explicitly states that it “has at all times denied and continues to deny any and all alleged wrongdoing and liability,” including the preposterous claim that Apple was actively selling Siri recordings to advertisers to target its users with customized ads.

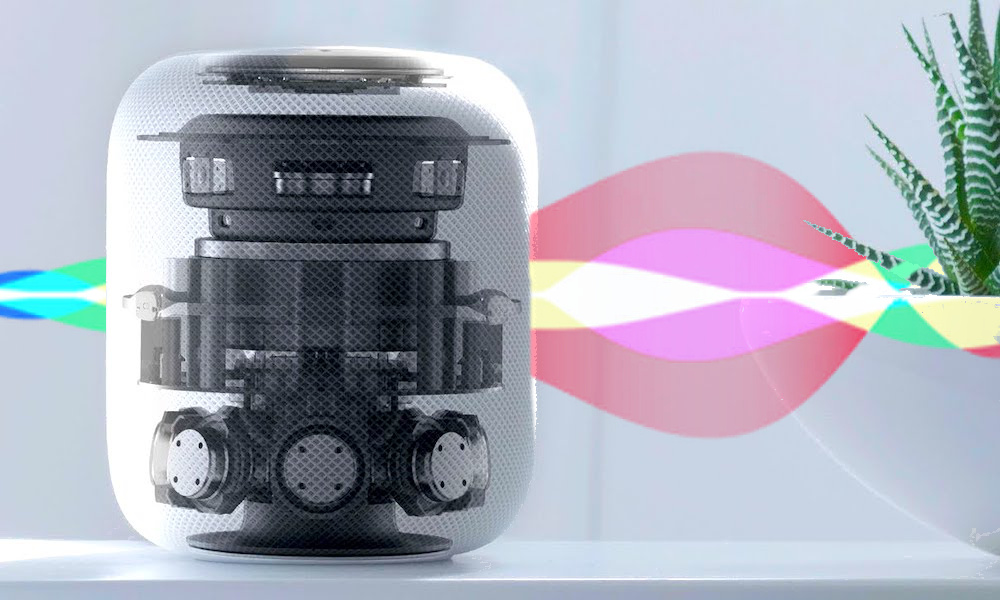

The crux of the initial lawsuit stemmed from a 2019 incident in which an Apple contractor came out and revealed to The Guardian that they had been hired to listen to recordings triggered when Siri was inadvertently activated — from situations where a HomePod, iPhone, or other Apple device mistakenly thought it heard someone say “Hey Siri.”

Apple has never denied these particular allegations, at least in broad terms. The company had long made it clear in its privacy policies that it may collect and analyze anonymized recordings to improve Siri. Granted, few people take time to read that fine print, but Apple still wasn’t making a secret of it.

However, the problem in this scenario is that Apple had collected recordings that its customers hadn’t explicitly consented to. These recordings weren’t from folks calling up Siri and asking it something, but rather from times when a device could be listening in to other random conversations because it thought it heard the wake phrase.

These recordings were anonymized — stripped of any personally identifiable information such as an Apple ID, device ID, or IP address — and then sent to employees and contractors for analysis with the goal of improving Siri and preventing these false positives.

Unfortunately, as diligent as Apple was about removing digital identifiers on these recordings, it couldn’t do anything about the content in the recordings themselves. If Siri picked up someone saying their name or address or discussing a confidential medical or legal matter, that was in the recording. It’s never been entirely clear how much of that sensitive information was traceable to specific individuals — for example, a conversation with a doctor might be private, but unless names were mentioned, there’d be no way of knowing who was speaking to whom — but the fact that this was there at all was enough to raise concerns and spark a class-action lawsuit.

However, the lawsuit was tossed out in early 2021, with US District Judge Jeffrey White ruling that the plaintiffs hadn’t presented enough facts to demonstrate that they’d actually suffered any harm. For instance, none of them could prove that their private data was part of the collection; the entire case was based on the whistleblower report and the theory that they might have been harmed.

The case was dismissed without prejudice, so the plaintiffs did their homework and later re-filed it with some more specific claims. Among these was the allegation that Apple was selling Siri data to third parties. This was based on users receiving targeted ads for things they believed were part of private discussions.

For example, one Siri user cited in the case claimed he began receiving ads for a “brand name surgical treatment” after discussing it privately with his doctor. Two others indicated that they received ads for Air Jordan Sneakers, Pit Viper sunglasses, and Olive Garden only after discussing these in the proximity of their Apple devices.

Siri Data ‘Has Never Been Sold’

This is the part of the argument that Apple most wants to distance itself from, especially after last week’s announcement prompted a raft of the usual conspiracy theories insisting that Apple was settling to avoid revealing its nefarious relationship with advertisers.

To make things absolutely clear, the company has released a statement explicitly stating that it does not sell Siri data — period.

Siri has been engineered to protect user privacy from the beginning. Siri data has never been used to build marketing profiles and it has never been sold to anyone for any purpose. Apple settled this case to avoid additional litigation so we can move forward from concerns about third-party grading that we already addressed in 2019. We use Siri data to improve Siri, and we are constantly developing technologies to make Siri even more private.

Apple

The other part of the statement — that Apple doesn’t use Siri to build marketing profiles — should be obvious to anyone who understands Apple’s business model. Apple has never been in the targeted advertising business. Its brief dalliance with advertising in the form of its long-defunct “iAd” service was merely a way to host ads and take a cut of the revenue from other advertisers, not build its own Google data machine.

Then What’s Going On Here?

Since Apple settled out of court, the plaintiffs didn’t have a chance to present their evidence. However, the allegations in the filing appeared to be circumstantial at best.

Assuming the claims made by the plaintiffs were sincere and aren’t a result of the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon — the increased likelihood of noticing an ad for something you’ve recently spoken about — there are plenty of other ways that private conversations could have found their way to advertisers that have nothing to do with Siri or Apple — at least not directly.

Most people’s iPhones have other apps created by companies that are very much in the advertising business, and there’s evidence to suggest that Facebook and Instagram actively listen in whenever possible. Apple’s privacy features prevent apps from getting carte blanche access to your microphone, many folks willingly grant this access for apps like Facebook Messenger, since it’s widely used to make voice and video calls — both of which require the mic. Once you’ve given an app permission to use your microphone, there’s no guarantee it won’t be listening in whenever you have it open (or have recently had it open).

I used to be skeptical about this, often assuming it was based on confirmation bias and select attention, as described above. However, a few months ago I was surprised when the passing mention of a highland sheep to my daughter resulted in two weeks of endless ads on Facebook for everything from t-shirts to keychains featuring highland sheep. That conversion came up while I had Facebook Messenger open to chat with someone else — and you can bet I switched microphone access off not long after that.

That incident stands out as unique. Despite having HomePods actively listening for Siri requests in nearly every room of my home, I’ve never once received niche ads related to any other conversations I’ve had. There’s little doubt in my mind that Facebook was the culprit here.

Apple has staked a big part of its reputation on preserving user privacy. It’s one of the ways it distinguishes itself from most other tech companies, and it strives to make that a selling point of being in the Apple ecosystem. It’s also easy for Apple to do this, as its business model doesn’t rely on traditional advertising; unlike its competitors, Apple’s key services, like Apple TV+ and Apple Music, don’t even have ad-supported tiers. It’s ludicrous to assume it would risk its reputation by selling out its customers to advertisers.