Judge Dismisses Copyright Lawsuit Against Apple Over Racially Diverse Emoji + Skin Tones | Here’s Why

Credit: Emojipedia

Credit: Emojipedia

Toggle Dark Mode

A U.S. District Judge has just dismissed a lawsuit that attempted to claim that Apple infringed on another company’s copyrights when it added racially diverse emoji to iOS 8.3 in 2015.

The lawsuit was brought against Apple in 2020 by Cub Club Investment (CCI), the developer of a 2013 app called iDiversicons, which was arguably the first app to introduce the concept of using different emoji stylings to reflect racial diversity.

While it’s not entirely clear why Apple was being specifically targeted in this lawsuit, since the new emoji were adopted by the Unicode Consortium, but it appears to stem from some past history between the original developer of iDiversicons, Katrina Parrott, Apple, and the App Store.

As The Washington Post reported last year, Parrot created the iDiversicons app after her oldest daughter came home from college complaining that the limited slate of emoji at the time didn’t allow her to express herself using her own racial identity.

iDiversicons was designed to address this issue, providing a slate of pseudo-emoji with five distinct skin tones that could be copied and pasted into messages. While these didn’t have the flexibility of actual emoji, since they weren’t part of the Unicode standard, the app was able to make them work similar to how Apple’s Memoji characters function today, by allowing users to basically paste them in as small images.

Not long after releasing the app, Parrott approached the Unicode Consortium with her idea for creating emoji with different skin tones, and submitted a proposal in 2013. Unicode invited her to present her ideas, which were reportedly well received from all the big tech players at the meeting, including Microsoft, Google, and Apple.

In May 2014, Parrott was in a conference room in the corporate offices of Adobe, which was hosting Unicode’s quarterly meeting, in San Jose. Parrott, the only Black person in the room, submitted 536 diverse emoji for consideration, including hand gestures with different skin tones and people representing different ethnic groups, to prominent figures such as President Barack Obama and former South African president Nelson Mandela.

The Washington Post

At the meeting, a senior software engineer from Apple also invited Parrott to visit Apple’s headquarters in Cupertino to pitch her idea directly to the iPhone maker. Parrott believed that this would lead to a licensing deal with royalties or a contract in which she would provide the new emoji designs for the iPhone.

A few months later, in August 2014, Parrott attended another Unicode meeting where the consortium members decided to go with five additional skin tones, in accordance with Parrott’s proposal. However, the group also decided that it was important to base the skin tones on some kind of standard, and as such decided to use the Fitzpatrick scale, a spectrum developed in 1975 that estimated the response of different types of skin to ultraviolet light.

Unicode Consortium President Mark Davis later emailed Parrott making it clear how essential she was to the team in developing the idea for diverse emoji, however that appears to be where Parrott’s contributions ended. In October, Apple contacted her to let her know that it would be using “its own team of human interface designers” to “handle all aspects of the emoji design.”

When Apple introduced the new emoji in 2015, Parrott became concerned that this would negatively impact her app, since of course many of the benefits offered by iDiversicons were now built into iOS 8.3. Parrott’s contact at Apple tried to help her out by going to the company’s marketing department to see if they would at least be willing to promote iDiversicons. They ultimately declined to do so, however.

Facing $200,000 in out-of-pocket expenses, Parrott decided to take the matter to court, insisting that she had been pushed aside by the technology giant, which took her ideas and used them to make her app obsolete.

Case Dismissed

While Parrott’s intellectual property lawyer tried to make this out to be a case of simple values of inclusion and exclusion, Apple took its usual pragmatic approach, stating that Parrott has no claim to the copyright over the simple idea of using different skin tones for emoji.

In court, Apple’s lawyers argued that “copyright does not protect the idea of applying five different skin tones to emoji because ideas are not copyrightable.” The company maintains that it developed the diverse emoji independently and did not copy Parrott’s work.

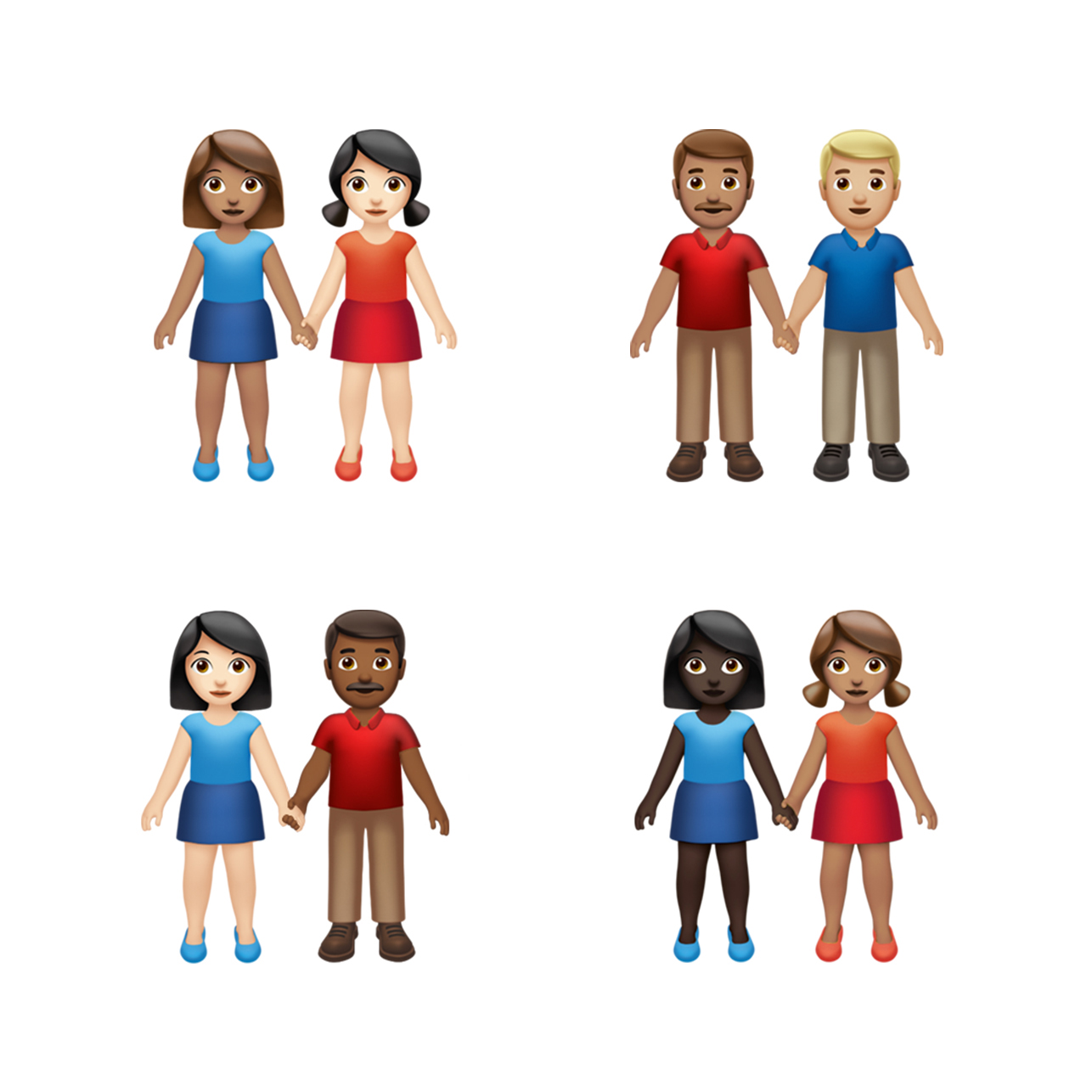

It’s a fair statement on Apple’s part, since even Parrott told The Washington Post that she was disappointed with what Apple ultimately came up with, as they didn’t look how she had imagined they would. For instance, Parrott had pushed at the Unicode meetings that racially diverse emoji should be about more than skin colours; that the emoji should also reflect the “difference in ethnicities.” An emoji depicting a Black person should have different hair than an emoji for a white person, she said.

Of course, this isn’t what Apple, and the Unicode Consortium, ultimately adopted, so it’s pretty easy to make the argument that it didn’t copy Parrott’s designs, and U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria agrees.

As reported by Reuters, Judge Chhabria handed down a ruling this week, stating that Cub Club Investment failed to show that Apple “copied anything that was eligible for copyright protection.”

There aren’t many ways that someone could implement this idea. After all, there are only so many ways to draw a thumbs up. And the range of colors that could be chosen is similarly narrow—only realistic skin colors (hues of brown, black, and beige, rather than purple or blue) fall within the scope of the idea.

U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria

Since the options for producing the idea of racially diverse emoji are very limited, Chhabria notes that they’re “entitled to only thin copyright protection against virtually identical copying.”

However, Chhabria ruled that Apple’s emoji are not “virtually identical” to Cub Club’s, as the plaintiff had alleged in its complaint. He noted differences in the gradient and coloring, as well as the shapes and shadowing.

Compared side by side, there are numerous differences. Whereas Cub Club’s emoji are filled in with a gradient, the coloring of Apple’s emoji are more consistent. The shape of Apple’s thumbs-up emoji is cartoonish and bubbled, while Cub Club’s is somewhat flatter. Many of Cub Club’s emoji have shadows; Apple’s do not. Even the colors used are distinct—although both Cub Club and Apple have chosen a variety of skin tones ranging from dark to light, the specific colors vary.

U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria

Chhabria added that at most, Apple copied Cub Club’s “idea’ of diverse emoji, but as Apple argued, U.S. law does not allow ideas to be copyrighted. Chhabria’s order does concede that “in the interest of caution,” Cub Club will have the opportunity to submit an amended complaint. However, he also adds that, having already seen the emoji side by side, “the Court is skeptical” that an amended complaint will succeed. If Cub Club fails to file an amended complaint within 14 days, however, the case will be “dismissed with prejudice” — that is to say, permanently.