Critical WhatsApp Flaw Exposes Billions of Phone Numbers

Eyestetix Studio / Unsplash

Eyestetix Studio / Unsplash

Toggle Dark Mode

In what could have been one of the largest data leaks in history, a massive security flaw in WhatsApp has just exposed 3.5 billion phone numbers — effectively encompassing every user of the messaging service.

To make matters worse, this exploit relies on an issue that Meta has known about since 2017 — yet failed to address with even the simplest fixes.

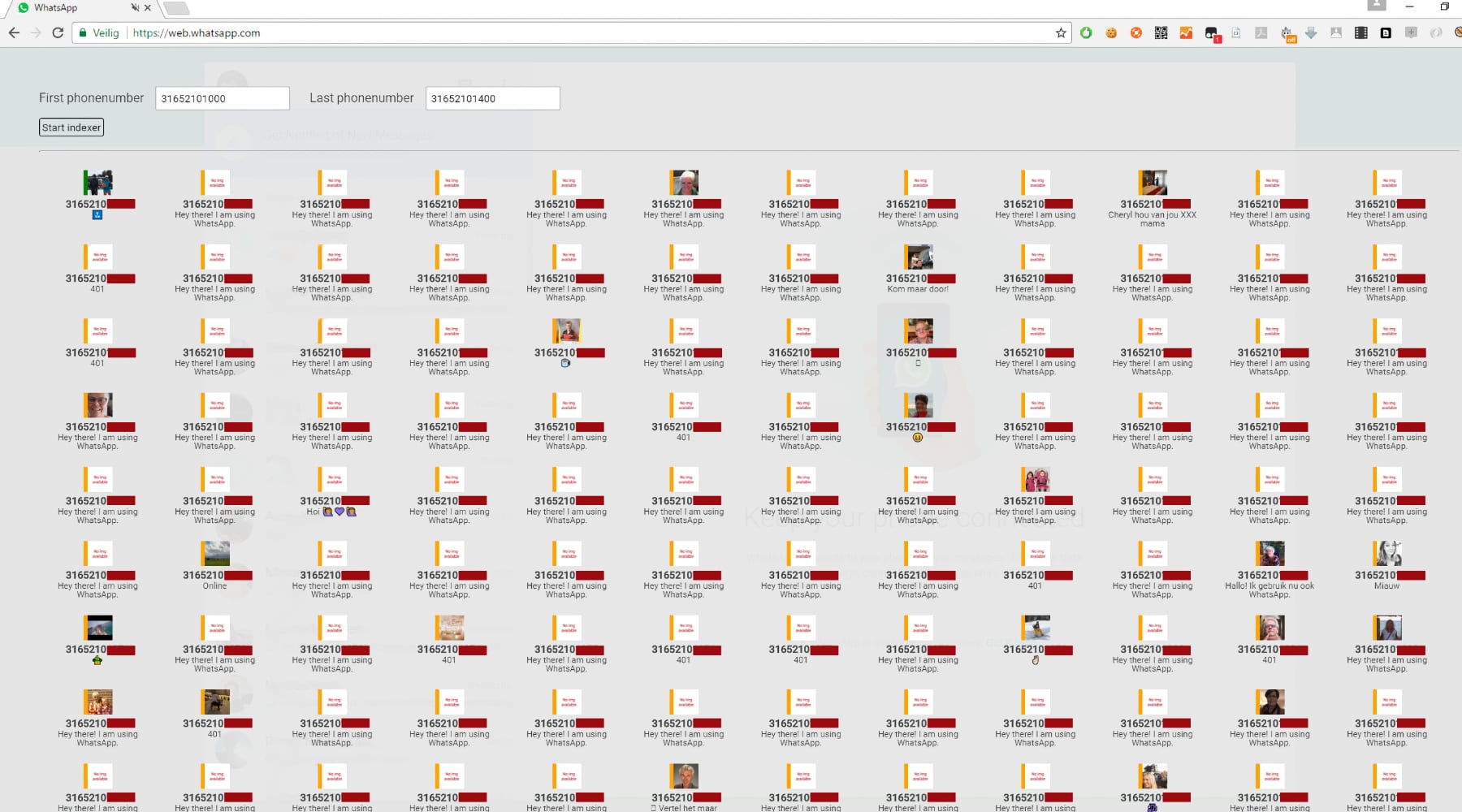

According to Wired, security researchers took advantage of what was effectively a brute force attack: feeding every possible phone number into WhatsApp’s contact discovery feature and compiling a list of which ones matched up to existing WhatsApp users.

It’s a ridiculously simple attack that exploits the user-accessible design that made WhatsApp popular in the first place. After all, a social media or messaging service is only useful if you can find people to chat with, and WhatsApp has always made that as easy as entering their phone number.

A Feature Without Guardrails

It’s a great feature, but WhatsApp never put up any guardrails around it:

Repeat that same trick a few billion times with every possible phone number, it turns out, and the same feature can also serve as a convenient way to obtain the cell number of virtually every WhatsApp user on earth—along with, in many cases, profile photos and text that identifies each of those users. The result is a sprawling exposure of personal information for a significant fraction of the world population.

Andy Greenberg, Wired

Something as simple as “rate limiting” would have made it much more difficult to use this technique to extract even millions of phone numbers, much less billions — or, in this case, all of them. However, a group of Austrian researchers found that WhatsApp was happy to keep churning out responses as quickly as numbers could be submitted.

Wired notes that the researchers were able to use this to not only extract 3.5 billion phone numbers from the service, but also obtain profile photos for about 57 percent of those, or over 2 billion users. The text on user profiles was also available for about a billion of those users.

To be clear, no messages or other private data were exposed here, merely phone numbers, profile pictures, and profile text — information that WhatsApp users had made or left publicly accessible. Still, the idea of a bad actor compiling a database of billions of WhatsApp users is a bit chilling — especially when you also consider that many of the numbers belonged to users in countries like China and Myanmar, where WhatsApp is officially banned.

Fortunately, this particular flaw was discovered by the good guys as part of a “responsibly conducted research study,” as described in a paper documenting their findings. That said, it’s impossible to be certain that a bad actor hasn’t already discovered and exploited this method for nefarious purposes. “If this could be retrieved by us super easily, others could have also done the same,” said Max Günther, another researcher from the university who co-authored the paper.

“To the best of our knowledge, this marks the most extensive exposure of phone numbers and related user data ever documented,” Aljosha Judmayer, one of the researchers at the University of Vienna who worked on the study, told Wired.

A Known Vulnerability Ignored Since 2017

A different researcher from the Netherlands, Loran Kloeze, informed Meta of this flaw in 2017, presenting a frightening scenario in which data exposure could be used to determine when people are online and even tie billions of profile pictures into facial recognition systems. Yet despite these dire warnings, Meta told Kloeze the system was working as designed, exposing only public information, and it was up to WhatsApp users to lock things down if they didn’t want their profile photos publicly exposed.

This is the kind of flaw that should have been easily addressed a long time ago, since there’s no conceivable situation where any single WhatsApp user needs to look up even hundreds of phone numbers an hour, much less hundreds of millions.

Meta told Wired that it had “implemented evolving defenses against scrapers, including rate-limiting and machine-learning techniques to ban scrapers.” Yet the researchers still managed to query roughly 100 million numbers an hour through WhatsApp’s browser-based app.

The good news is that it appears Meta has taken notice this time — even if it meant the researchers had to create a database of billions of phone numbers and profile photos to make their point. The group warned Meta of their findings in April and deleted their copy of the 3.5 billion phone numbers. Last month, they confirmed that the company had fixed the problem by implementing stricter rate-limiting measures.

Meta told Kloeze in 2017 that his discovery wasn’t eligible for Meta’s bug bounty program, and it’s unclear whether the Austrian researchers, who reported their discovery through the same channels, will be compensated for finding it. However, Meta issued a statement to Wired thanking the researchers, while minimizing the impact by describing the data as “basic publicly available information,” and reiterating the point that WhatsApp users are responsible for securing their personal profile information.

Nitin Gupta, vice president of engineering at WhatsApp, credited the researchers for helping it “stress-test” the defences it’s already working on, adding that “We have found no evidence of malicious actors abusing this vector. As a reminder, user messages remained private and secure thanks to WhatsApp’s default end-to-end encryption, and no non-public data was accessible to the researchers.”

Anomalies in the Encryption Keys

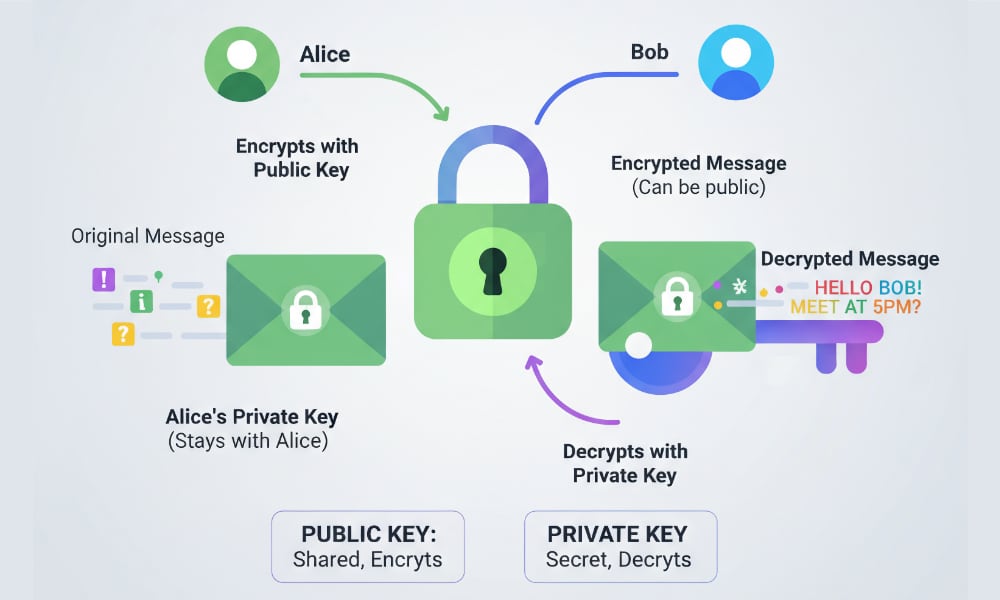

Nevertheless, the team of researchers from the University of Vienna also found concerning issues with the cryptographic keys used by WhatsApp. The public keys for all 3.5 billion accounts were exposed via the same enumeration method that confirmed phone numbers and pulled many profile photos. Public keys are only one half of the cryptographic handshake, used to encrypt a message that’s sent to a recipient; the second, “private” half is required to decrypt it. As a result, public keys are intended to be public.

However, the researchers had the rare benefit of a massive sample of WhatsApp cryptographic keys — basically all of them — providing unique insight into anomalies that would otherwise remain hidden. Specifically, they found that the same keys were duplicated across a surprising number of accounts.

Two users with the same key could technically decrypt each other’s messages, but they’d first need access to each other’s actual message data, making this more of a theoretical vector for targeted attacks by skilled hackers than something that a normal WhatsApp user would stumble into.

While this discovery gave the researchers pause, it doesn’t appear to affect standard users, and they’re not convinced it indicates a flaw in WhatsApp’s design. Many of the accounts they found with repeated cryptographic keys appeared to have been created by scammers and may have been using unauthorized WhatsApp clients, which wouldn’t conform to WhatsApp’s standards.

Ultimately, the biggest problem, the researchers note, is not technical, but rather logistical. Phone numbers simply shouldn’t be used as unique identifiers for a service as large as WhatsApp, because their predictability makes brute-force discovery attacks like this trivial. “If you have a big service that’s used by more than a third of the world population, and this is the discovery mechanism, that’s a problem,” said Judmayer. If anything, the surprise isn’t that this happened — it’s that it didn’t happen sooner.