Medical Researchers Warn the Apple Watch Is an Unreliable ‘Black Box’ for Health Studies

Credit: Chinnapong / Shutterstock

Credit: Chinnapong / ShutterstockToggle Dark Mode

Even though the Apple Watch is commonly used in many medical studies, it seems that at least some researchers are now reconsidering the use of Apple’s wearable due to the closed nature of the algorithms used to produce accurate health data.

According to The Verge, the problem is that the Apple Watch is effectively a “black box” when it comes to how the raw measurements captured by its various sensors are translated into usable data for doctors, scientists, and other medical researchers.

While many researchers haven’t put much thought into this, associate professor Jukka-Pekka Onnela, who teaches and studies biostatistics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, decided to investigate exactly how serious the data issues could be when it comes to commercial wearable devices like the Apple Watch.

Onnela normally shies away from using commercial wearables in research studies, opting instead for more expensive research-grade devices that are certified to a much higher degree of accuracy. However, when a collaborative study with the department of neurosurgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital proposed using the Apple Watch, Onnela deduced that he needed to find out exactly what he was getting into before beginning the study.

Same Data, Different Results

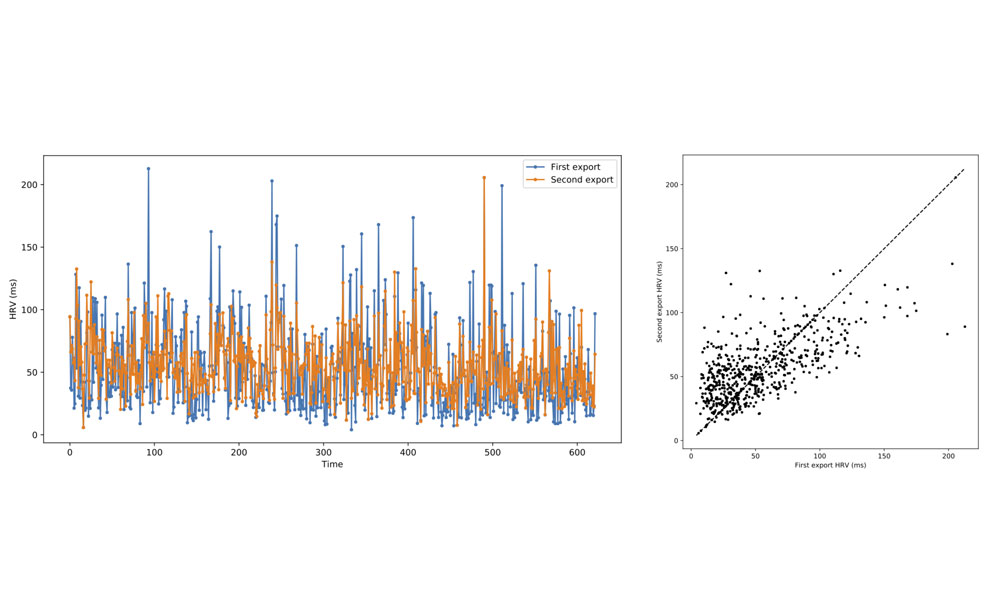

Hassan Dawood, a research fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, made two separate exports of the same daily heart rate variability data from his Apple Watch, several months apart. The first export was made on September 5, 2020, while the second was made on April 15, 2021.

Dawood and Onnela compared the data between the two exports from the same stretch of time — early December 2018 to September 2020, and discovered significant differences — even though it all came from the same raw data.

The differences proved Onnela’s hypothesis — that the “black box” of wearable algorithms exists and poses a problem — but even Onnela, who has long studied the phenomenon, was shocked by the differences.

What was surprising was how different they were. This is probably the cleanest example that I have seen of this phenomenon.

Jukka-Pekka Onnela, Associate Professor of Biostatistics, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

Onnela published his findings in a blog post, where he outlines the statistical differences, including a scatter plot that shows just how inconsistent the data really was.

One would assume that downloading data for the same period twice should return the same data. After all, nothing about the behavior has changed for the historical data, it just happened to be downloaded at two different points in time. In the experiment below, we discover that when downloading data for a specific time period at two different points in time, we get strikingly different data sets.

Jukka-Pekka Onnela, Associate Professor of Biostatistics, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

While the study doesn’t specify what versions of watchOS were being used at the time of each export, the dates suggest that they likely crossed over a major watchOS update.

Apple didn’t release watchOS 7 until September 16, 2020, which means that Dawood’s Apple Watch would have been running some version of watchOS 6 — potentially 6.2.8 —when the first export was made on September 5, 2020.

By April 15, 2021, Apple had already updated watchOS 7 several times, with version 7.3.3 being the most current one. It’s unclear, however, whether Dawood had updated his Apple Watch prior to each export.

Somewhere along the way, however, Apple obviously changed the algorithms used to analyze the raw heart variability data that had been collected by the Apple Watch.

The real problem, of course, is that Apple doesn’t provide any way for researchers to access the raw data recorded by the wearable’s sensors. Instead, they’re forced to rely on the data that’s already been analyzed and filtered through an algorithm of some kind. It’s the medical data equivalent of the differences between a RAW photo and a JPEG that’s been processed by Apple’s computational photography algorithms.

Tainted Results?

Scientists who study sleep patterns have been dealing with this problem for years, but this is the first time that scientists have actually attempted to quantify it.

In fact, University of Michigan researcher Olivia Walch has long suspected that the data that gets filtered through a device’s software is unreliable, but now she has a better understanding of how much of a problem it can actually become.

Walch adds that the constantly changing algorithms make it extremely impractical to use commercial wearables for sleep research, which effectively drives up the costs of these studies as scientists need to turn to more accurate — and expensive — equipment.

Are you going to be able to strap four FitBits on someone, each running a different version of the software, and then compare them? Probably not.

Olivia Walch, Post-doctoral Research Fellow, University of Michigan Department of Neurology

In research, it’s critically important that studies be able to produce consistent results, and with software algorithms that can change the data so drastically, it’s difficult for any studies that use commercial wearables to come to any definitive conclusions.

For example, as Walch points out, somebody could run a study on sleep patterns using an Apple Watch running watchOS 7.1 and come to an entirely different set of conclusions than a study performed using watchOS 7.2. Since researchers don’t get access to the raw data, and Apple doesn’t tell anyone about the changes it makes, there’s simply no way of knowing.

Maybe you would have a completely different result if you just been using a different model.

Olivia Walch, Post-doctoral Research Fellow, University of Michigan Department of Neurology

In the case of Onnela’s study with Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the results from Dawood’s Apple Watch data was enough to scrap the team’s plans to use the Apple Watch in the study. Onnela says that for researchers to be able to rely on commercial wearables, the raw data must be available, or at the very least companies like Apple need to provide advance notice and documentation when algorithms are changed.