Apple and Google Partner to Fight COVID-19: 5 Things You Need to Know

Credit: Apple/Google

Credit: Apple/Google

Apple has been leading the way in the fight against the novel coronavirus in a whole lot of different ways, ranging from simply preventing false and misleading apps on the App Store to donating large amounts of cash to organizations ranging from those providing meals to worldwide relief efforts, producing face shields for medical staff and helping to obtain masks.

Naturally, however, the company has also been doing what it can on the digital front, releasing its own COVID-19 app in partnership with the CDC and FEMA, and now it's about to take another huge step forward with the announcement of a new coronavirus tracking system that will be built into iOS devices. Continue reading to learn everything you need to know about this incredible new partnership.

How Does It Work?

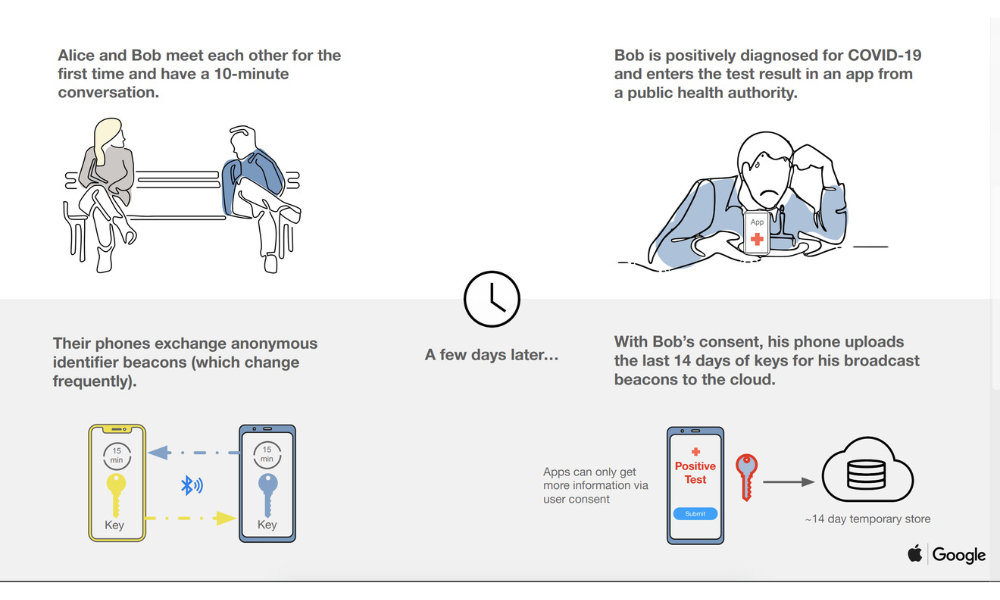

Apple announced the new program today, in which it’s actually partnering with Google to build a system into both iOS and Android devices that will use Bluetooth Low Energy to allow users to easily share data and apps from approved medical and government organizations, along with building out a voluntary contact-tracing network.

This latter feature would be similar to the solution that Singapore released a few weeks ago, but would have the major advantage of being built into every iOS and Android device running the latest versions of their respective operating systems.

What Is Contact Tracing?

Due to the long incubation period of the novel coronavirus, many medical officials agree that one of the key tools in the fight against COVID-19 is to be able to trace everybody that an infected person may have come into contact with — even before they knew they were infected. Since it can take up to 14 days before somebody begins showing symptoms of COVID-19, that could potentially be a lot of people, even in these days of social distancing.

Obviously it can be very hard to remember everybody you’ve come into contact with over the course of two weeks, and as a result many organizations have been looking to technology to help track these interconnections. In fact, Singapore developed an app last month called TraceTogether that did exactly that, by using Bluetooth signals between participating mobile devices — those that have the app installed — to create a list of who they’ve come into close contact with.

As great of an idea as TraceTogether is, however, it suffers from the fact that the vast majority of people won’t ever both to install the app, so the information it provides wouldn’t be comprehensive by any means.

By contrast, the strategy that Apple and Google are adopted is to make it a standard feature of every single iOS and Android device, so that every iPhone and Android smartphone will be able to keep track of every other iPhone or Android smartphone that it’s come within a few feet of.

According to the announcement, this data will be collected and stored in such a way that it will only be accessible to official apps from public health authorities, which will provide a way for users to report if they’ve been diagnosed with COVID-19, which can then in turn alert other people that may have come into contact with that infected person.

The Plan

Apple and Google are planning to release new APIs in May that will allow official apps from public health authorities to interact with the system, giving developers from those organizations a chance to update their apps and test the integration and leverage it for their own contact tracing features.

At this stage, it will be possible for official apps to perform contact tracing, but much like Singapore’s TraceTogether app, it will only be available for those who are using the relevant apps, meaning that you won’t know if you may have come into contact with an infect person unless they also happen to have been running a compatible app.

Following that, however, Apple and Google will work together to build the Bluetooth-based contact tracing in at the operating system level, and although participation will still be voluntary, it will allow more users to opt-in through a much simpler process, as well as allowing more government and health apps to tie into the data.

What About Privacy?

Of course, developing a solution like this opens up a Pandora’s box of privacy concerns, and Apple is taking its usual meticulous steps to build the technology in such a way that even those who sign on for contact tracing won’t have to worry about giving up their privacy.

In fact, Apple has published a page titled Privacy-Preserving Contact Tracing where it offers up some draft technical documentation explaining how its all going to work, and specifically outlining the steps it will be taking to protect user privacy:

- The Contact Tracing Bluetooth Specification does not require the user’s location; any use of location is completely optional to the schema. In any case, the user must provide their explicit consent in order for their location to be optionally used.

- Rolling Proximity Identifiers change on average every 15 minutes, making it unlikely that user location can be tracked via Bluetooth over time.

- Proximity identifiers obtained from other devices are processed exclusively on device.

- Users decide whether to contribute to contact tracing.

- If diagnosed with COVID-19, users consent to sharing Diagnosis Keys with the server.

- Users have transparency into their participation in contact tracing.

In other words, in addition to having to opt in to participate in contact tracing in the first place, all data on who you’ve come into contact with remains stored on your device as a form of random device IDs that are entirely meaningless to anybody but the systems being run by Apple and Google. Further, even if you are diagnosed with COVID-19, you have to explicitly consent to sharing that fact — the reporting isn’t automatic.

However, Apple makes it clear that no GPS data is used, as there’s no real need for contact tracing to know where you are to figure out who you’ve come into contact with. In this case, it simply picks up the signals of nearby phones are regular intervals, storing a somewhat anonymized list of them in a database.

Final Thoughts

Digging into the technical details, the solution appears to be similar in concept to how Apple’s Find My feature keeps your device location private, which will also likely factor into protecting the privacy of Apple’s upcoming AirTags. The bottom line is that neither Apple nor Google will be maintaining a master database of which phones have been in contact with each other.

While the system isn’t without its problems, such as flagging false positives in crowded areas, and possibly even in adjacent apartments, it still seems likely to offer more positive benefits overall, although it will likely supplement the more traditional methods of contact tracing — asking people where they’ve been and who they’ve come into contact with — rather than replacing it outright.