9 Hidden Ways Apple Protects Your Privacy Revealed

Wachiwit / Shutterstock

Wachiwit / Shutterstock

Pretty much everyone knows by now that Apple, among other tech giants of similar size, is the one that actually cares about and protects your privacy. The company has even taken advantage of this reputation in recent ads.

And to drive that point home, the Cupertino tech giant has revamped its privacy page with an incredible amount of detail about its various data policies.

But while many users probably skimmed that page, there are likely quite a few interesting tidbits that the average reader might have missed. Here are a few of them. Continue reading to learn 9 Hidden Ways Apple Protects Your Privacy.

Health Data Purging

One of the problems with data is that it can be hard to manage once it’s out. Say, for example, you start sharing a piece of data with another smartphone user. Once that data is on their own device, you’d think that it would be nearly impossible for it to be deleted from your end..

Apple has taken this into account for some more sensitive data metrics, such as shared Activity or Health data. According to the new privacy page, if you stop sharing this data, Apple will automatically purge it from any other shared device.

Encryption Everywhere

Those who are familiar with Apple’s iMessage or FaceTime standards probably know that they are end-to-end encrypted. But Apple’s new privacy page really makes it clear just how extensive Apple’s encryption policies really are.

Certain data in Maps and Health is also end-to-end encrypted, for example. But Apple also notes that it uses encrypted storage and encrypted data transmission for Home and Keychain data, as well. The same goes for any data sent to iCloud servers and vice versa.

Private Click Measurements

Many privacy-conscious users may already know about the ways that Safari automatically blocks tracking. But Apple’s Safari white paper actually includes an interesting tidbit about a little-known mechanism called Private Click Measurement.

It essentially prevents cross-site tracking, but still enables advertisers to measure campaign effectiveness. It’s basically the best of both worlds, allowing websites to maintain revenue streams while protecting user privacy. It also appears to be an Apple proprietary system — and the company has even proposed it as a new standard for the whole World Wide Web.

On-Device Siri Suggestions

With the recent Siri privacy debacle, many users are probably eyeing the Apple digital assistant with a bit more suspicion than before. How does Siri, for example, offer suggestions or other data without compromising Apple’s privacy stance?

Easy: it doesn’t send any of that data to Apple’s servers. Apple notes that when users ask Siri to read Messages or Notes, none of that data ever leaves their device. The same goes for certain suggestions in Safari and Maps. What about those suggestions in the QuickType keyboard? Well, those are also processed purely on your device.

Hefty Device Security

“Without security protections, there is no privacy,” or so says Apple’s updated webpage. After all, your data cannot be private if someone can simply compromise it. But Apple’s iOS security white paper reveals the multitude of ways that the company protects your digital security as well as your privacy, too.

To discourage brute force password cracking attempts, Apple entangles a device’s UID with a user’s passcode, for example. Apps on your iOS device are also sandboxed, so they cannot affect other apps or systems. Even Handoff and other Continuity features are protected by encrypted security keys. The security white paper is a long but eye-opening read.

Real User Indication

App developers and websites want to make sure that a real person is accessing and using their systems — that’s the entire point of captchas. The Sign In with Apple white paper reveals an interesting tidbit about how Apple balances this with its pro-privacy stance.

For example, the company uses on-device machine learning to ensure that you are using your device in a way that’s “consistent with ordinary, everyday behavior.” The system then generates a numerical score that’s sent to Apple, which is analyzed to determine if a real person is using the system. It’s an anti-fraud measure with baked-in privacy protections.

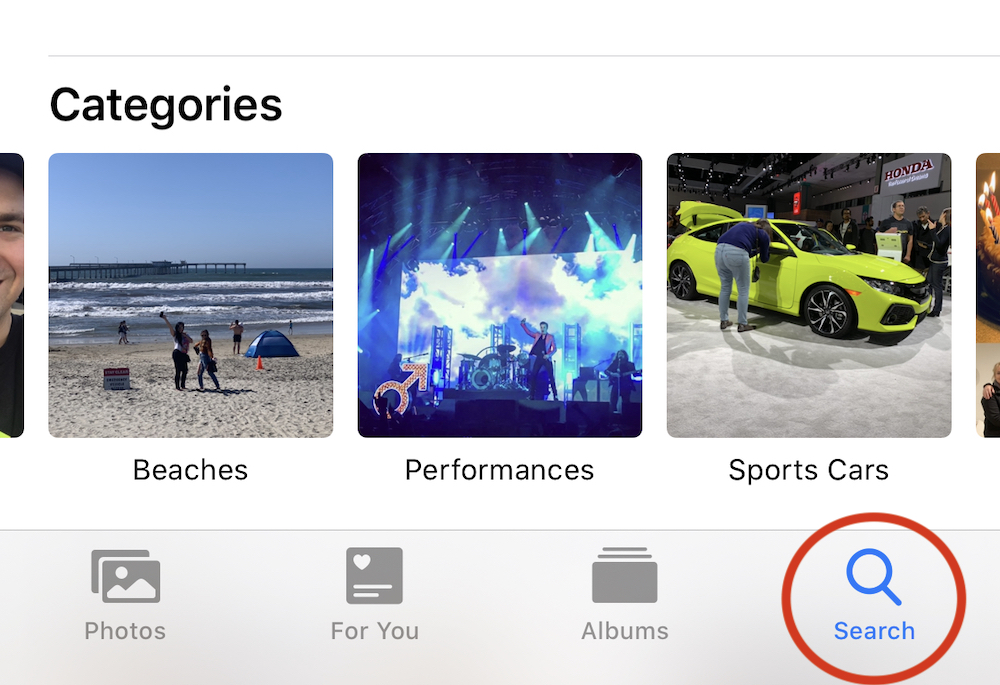

Local Photo Processing

Like other technology companies, Apple’s products analyze your photos to detect faces, scenes and other parts of the composition. The big difference here is that the vast majority of the photo processing and analysis on Apple products occurs strictly on-device.

Apple’s Photos white paper shows off just how far Apple goes to protect its users privacy without compromising the convenience of Apple devices. Using on-device intelligence, Apple itself never learns who or what is in the photos that you take. So you end up with cool and relevant Memories and Sharing Suggestions, but your data is still kept safe and sound.

Location Services

If you’ve used iOS 13, you’re undoubtedly familiar with just how prevalent location tracking via Location Services, Bluetooth or Wi-Fi really is. Thanks to the new alerts and options to disable it, users have much more agency over their location data. But that isn’t the end of it.

As a small example, Apple doesn’t let just every app see the names of the Wi-Fi network you connect to. There are other interesting non-privacy tidbits in the Location white paper, too. Like the blue “halo” that surrounds your marker in Maps. The smaller the halo, the more precise your location actually is.

Apple Pay Rewards Data

To protect Apple Pay users, Apple doesn’t actually use your real credit or debit card number. Instead, it generates a Device Account Number that’s encrypted and store on-device. That way, there’s absolutely no way for Apple to track your purchase history — so there’s no data that can be used to target ads.

But that’s not the only way Apple protects financial and transactional data. For example, if you use a rewards card in Apple Pay, Apple requires that merchants encrypt any personally identifiable information. More than that, no rewards information is ever shared with third parties without explicit user consent.