13 Memorable Apple Products That May Have Missed the Mark

Credit: Roman Tiraspolsky / Shutterstock

Credit: Roman Tiraspolsky / Shutterstock

There is no doubt that Apple has made some absolutely incredible products that have changed the face of technology. From the early Macintosh computers to the iPod and the iPhone, the company’s accomplishments are legendary, and even those who aren’t fans of Apple products have to concede that they’ve made a massive impact on the way we use computers and mobile devices today.

As the old saying goes, however, you can’t make an omelet without breaking a few eggs, and despite all of Apple’s meteoric successes, the company’s products don’t always hit the mark that they’re aiming for.

Every so often they’re simply too ambitious for the current market, while other times Apple releases products that it seems to think are a good idea, yet it failed to read the room, creating products that few people really want.

With the surging popularity of Apple’s flagship products today, it’s easy to forget that there were quite a few that were either too far ahead of their time or too niche to really catch on. Read on for 13 Apple products that missed the mark.

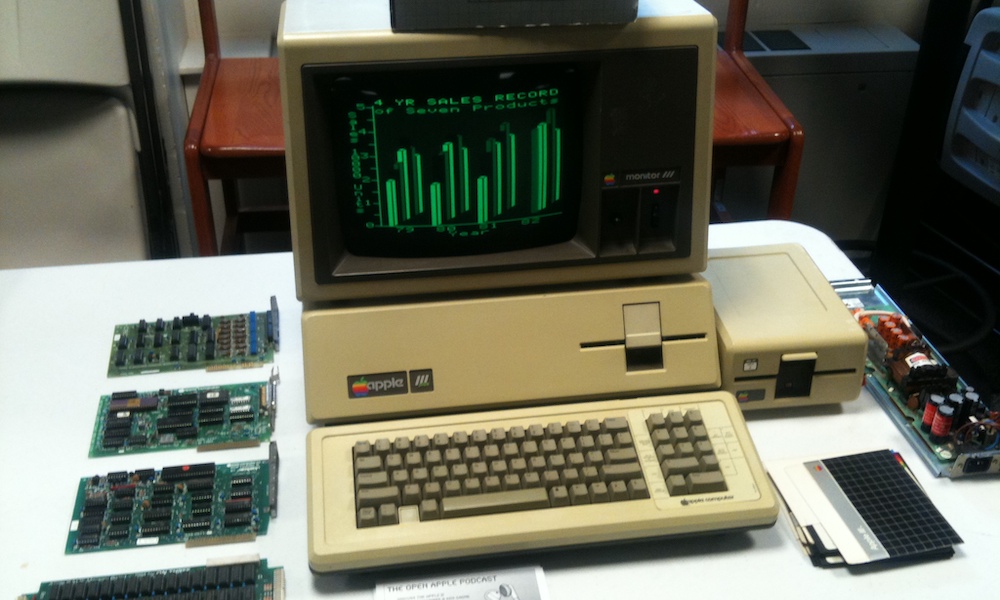

The Apple III (1980)

If you’ve never heard of the Apple III, there’s probably a good reason for that. Following the incredible success of the Apple II computer in the late seventies, the fledgling company decided to try to make lightning strike again with a third-generation model that turned out to be its first big commercial failure.

The Apple III promised to be the first business-class Apple computer, with an 80-character display and a mixed-case keyboard, both of which were upgrades from the giant 40-column text and all-uppercase design of the Apple II.

However, it took much longer to build than anybody expected, missing its target launch date by about six months, and then to make matters worse, the first batch of 14,000 machines had to be recalled due to serious stability issues, requiring Apple to overhaul the design entirely, with another version of the Apple III arriving a year and a half after it was originally supposed to be ready to go.

The Apple III was officially discontinued in early 1984, less than three years after the stable version went on the market on November 9, 1981. The reason for its failure? According to Apple’s co-founder Steve Wozniak, it was designed by the marketing department. The upside, however, is that the debacle with the Apple III forced the company to take a long, hard look at how it did things. Had it not flopped, the original Macintosh may have never seen the light of day.

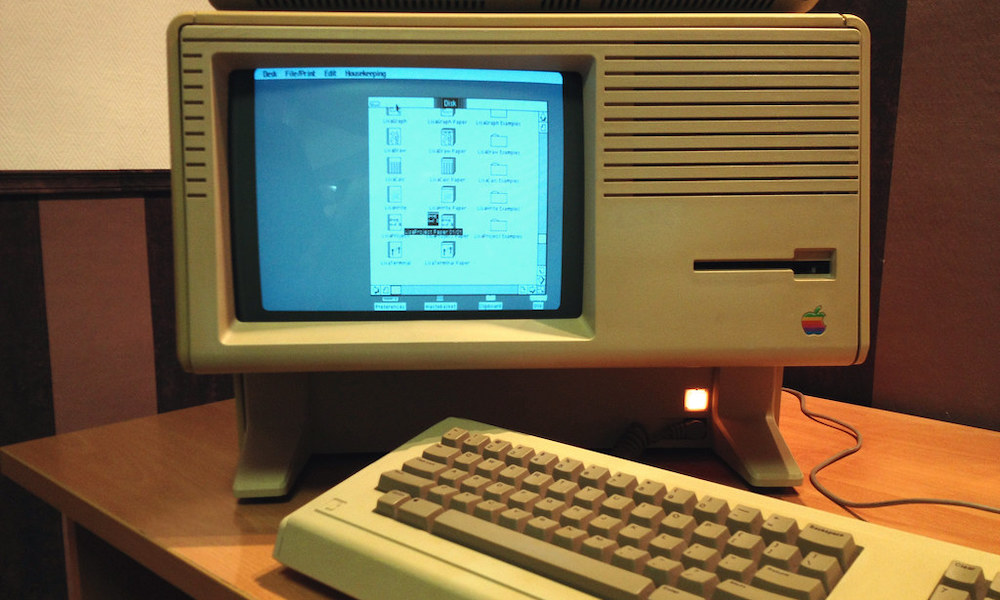

The Lisa (1983)

While traditional Apple computers stuck with a text-based monochrome display, Apple had another team working on a graphical user interface (GUI) at the same time. Both the Apple III and the Lisa were developed in parallel, although the latter didn’t come out until early 1983.

Officially, the name stood for “Local Integrated Software Architecture,” but that sounds like a pretty contrived acronym, and we’re sure it’s no coincidence that Lisa was also that name of Steve Jobs’ first daughter, who was born the same year the project began.

It was actually the first personal computer with a GUI, and arguably the spiritual predecessor to the original Macintosh. It was way ahead of its time technologically, introducing features like a high-resolution display, protected memory, a drag-and-drop interface, and an internal 5MB hard drive.

The problem, however, is that all this bleeding-edge technology didn’t come cheap. The Lisa debuted with a staggering $9,995 price tag. Dollar-to-dollar, that’s already more than a maxed-out 16-inch MacBook Pro with an M1 Max chip, or an entry-level Mac Pro. Convert that from 1983 dollars into 2021 dollars, though, and it works out to over $27,000 dollars in today’s money.

So, it’s probably not surprising that Apple only managed to sell about 10,000 Lisa computers, which resulted in a net loss of around $50 million on the project. The rest of the unsold inventory ultimately ended up in a landfill in Utah, where Apple hired security guards to ensure they were all properly destroyed in the process.

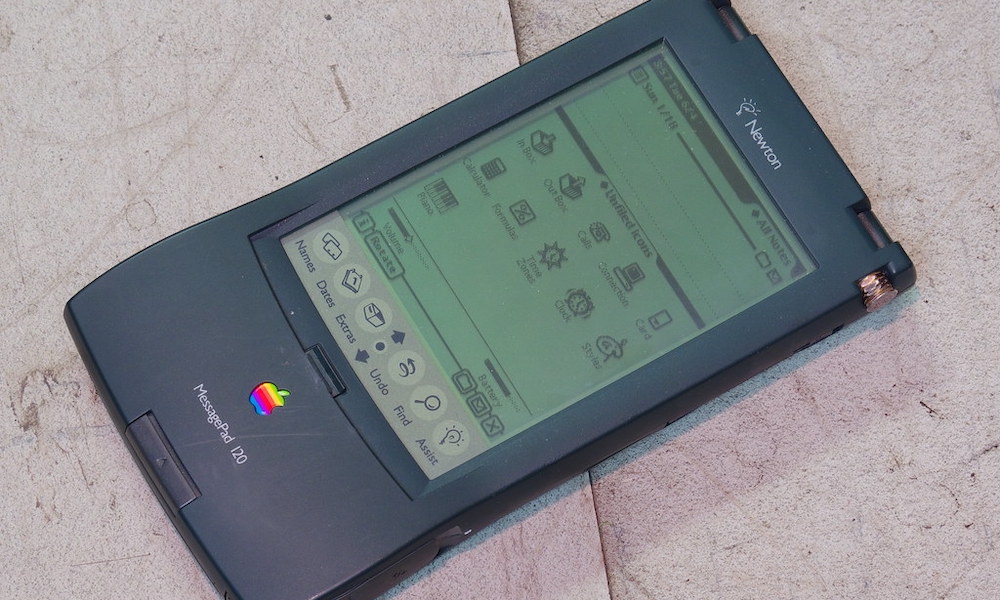

The Newton (1993)

Perhaps one of Apple’s most infamous early failures was its attempt at one of the first Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs). In fact, it was the Newton that created the category of personal digital assistants, with Apple’s then-CEO John Sculley coining the phrase later on in the product’s development cycle.

The Newton came to an era where most “personal organizers” were calculator-like devices designed simply to store your address book and calendar information. By contrast, the Newton offered a full “Newton OS” operating system that was the first to feature handwriting recognition.

Like the Lisa, Apple bit off way more than it could chew with the Newton. The handwriting recognition was unreliable at best, the user interface was slow, and it had no shortage of glitches. Developers also had to shell out $1,000 (in 1993 dollars) for the toolkit required to build apps for the Newton platform, which meant there was a serious dearth of third-party apps available for it.

The Newton also didn’t come cheap, with a starting price of $699 — equivalent to around $1,300 in today’s economy. Combined with all the device’s other problems, it’s easy to see why there really wasn’t much uptake. Other companies were inspired by the Newton, however, and modem maker U.S. Robotics took a less ambitious approach to introduce the first Pilot 1000, which eventually became the PalmPilot after it was sold to 3Com and then spun off into Palm, Inc.

To be fair, the Newton was created during Steve Jobs’ time away from Apple, and one of Jobs’ first acts upon returning to the company in 1998 was to kill the project off entirely. However, it’s easy to see how the lessons learned from the Newton helped to inspire the iPhone years later, at least as much of an example of what not to do when developing a mobile product. It probably explains much of Apple’s slow-and-steady iterative approach that continues with the iPhone and iPad to this day.

Macintosh TV (1993)

Back in the 1990s, technology companies were still trying to figure out exactly where the lines would be drawn between personal computers and entertainment devices. Graphical user interfaces had taken over, the CD-ROM was gaining traction, and the nascent World Wide Web was promising to change the way we communicated online.

Into this era came numerous attempts at all-in-one “media hub” computers that envisioned a world where the PC and the television set would overlap. Apple’s answer to this was the ill-fated “Macintosh TV,” a multimedia machine that it hoped would make the Mac more cool and approachable.

As a concept, it was a great idea — take a beige Macintosh LC 520, paint it black, and toss in a TV tuner card and remote. It failed miserably in its execution, however, since Apple capped it at only 8MB of RAM at a time when other Macs could go up to 32MB, and gave it a slower system bus as well. There was also no standard video output, and no picture-in-picture support.

Combined with the $2,099 starting price (~$4,000 today), this made the Macintosh TV a really hard sell. Most customers realized they could just buy a beige Mac and a standalone TV for far less and end up with a more versatile setup where they could actually watch TV and use their Mac at the same time. The Macintosh TV lasted about five months before Apple pulled it off the shelves.

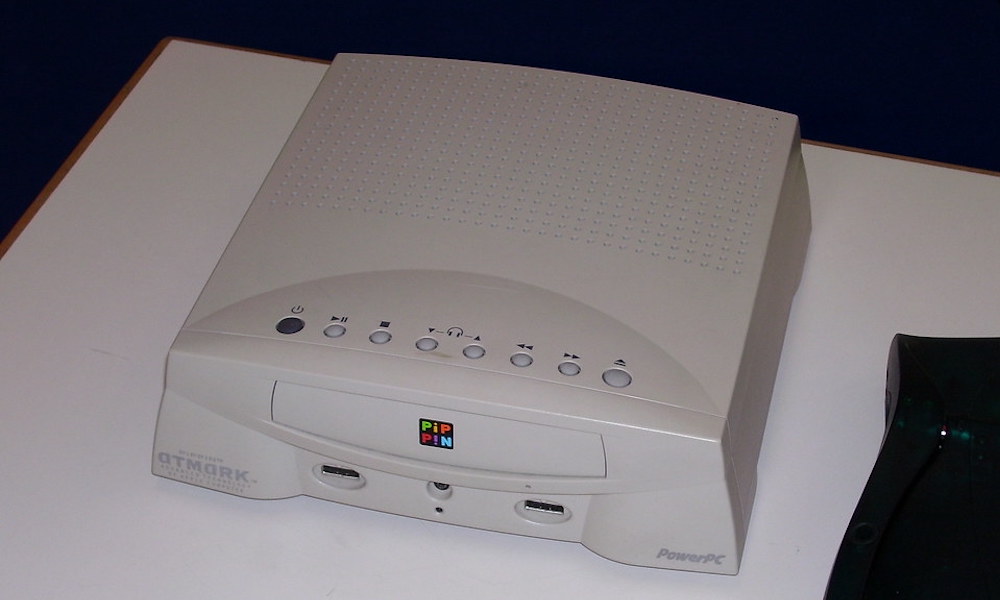

The Pippin (1996)

Despite the failure of the integrated Macintosh TV, the Scully-led Apple figured that it could still capture a slice of the entertainment market and get into users’ living rooms by building its own game console.

Apple teamed up with Japan’s Bandai, taking the guts of a Macintosh Classic II and tossing them into a Bandai-designed case to create what it hoped would become an open standard home entertainment and gaming platform. The goal wasn’t so much to sell the Pippin as it was to use it to increase the market share of the Macintosh.

Unfortunately, the idea never got very far. For one thing, it took too long to get off the runway, with Apple announcing the concept in 1994 but not actually releasing it until 1996, and even then only in Japan. It came to the U.S. in 1997 and sold for $599. The problem? Nobody except Bandai was making games for it.

In the end, it sold about 42,000 units — only 12,000 of which were to customers in the U.S. Meanwhile, the original PlayStation sold for half the price, and sold 100,000 units on the first day of its launch in 1994, and 102 million in its lifetime. Of course, it also had nearly 8,000 game titles available.

The Pippin, which was considered part of Apple’s “Macintosh clone” program, was shut down by Steve Jobs upon his return to Apple in 1997. Again, though, this probably didn’t come without Apple learning a few valuable lessons from the attempt, and the company returned with a reimagined living room strategy in 2007 with the original Apple TV.

The 20th Anniversary Mac (1997)

Apple was a far more nostalgic company in 1997 than it is today, and this was perhaps most obvious from its attempt to create a premium, luxury computer designed solely to mark the date of the company’s 20th anniversary.

The 20th Anniversary Macintosh was an impressive piece of technology, designed with an attempt at style that wasn’t seen on many other computers of the day. It was the first Mac with a flat-screen LCD, and also packed in a custom Bose sound system, an FM radio, a TV tuner, a CD-ROM drive, and even leather palm rests.

This was a limited-run special edition computer, and it carried a hefty price tag to match. At $7,499 (~$12,800 today), it didn’t get much uptake, even with a direct-to-door concierge delivery service included. Apple only made about 12,000 of these, but it had a hard time selling even those, and was forced to drop the price to $3,500 and then down to $1,995 a year later to try to clear out the last of its stock.

Even though many heralded the iPhone X as the “10th Anniversary iPhone,” it’s important to keep in mind that Apple never said any such thing about the device. Today it’s a company that looks forward, and not back, and it’s unlikely we’ll ever see another attempt at an “anniversary” product.

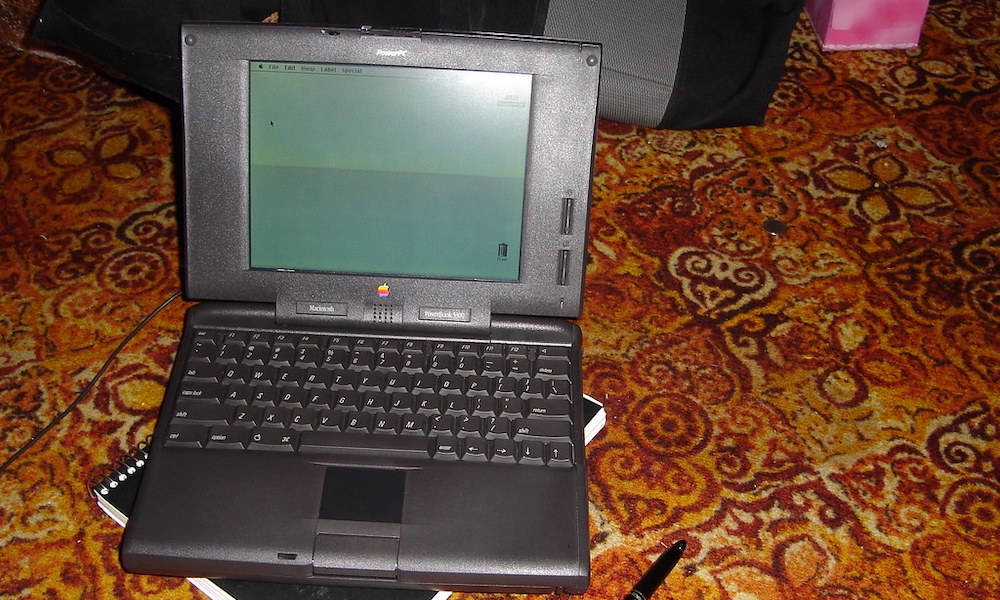

The PowerBook 5300 (1995)

Apple’s PowerBook laptops were quite successful in the early nineties, but once again the company got a bit too ambitious in its attempts to dominate the market.

The result was that PowerBook 5300, the first to use the PowerPC chips that would end up at the heart of all Apple’s Macs until its switch to Intel in 2006. Apple wanted to make this its smallest and most powerful laptop ever, and even added hot-swappable expansion modules and support for using an external monitor.

Unfortunately, Apple packed a bit too much into the 5300, resulting in design flaws that earned it a place among the worst Apple products of all time. It was one of the first laptops to actually become known for spontaneously bursting into flames. However, even users who were fortunate enough to avoid that problem encountered cracked cases, broken hinges, and frayed cables.

Unflatteringly dubbed “the HindenBook” by Apple fans, the PowerBook 5300 was discontinued after less than a year.

The Power Mac G4 Cube (2000)

Apple’s turn-of-the-millennium Power Mac G4 Cube is widely regarded as one of the company’s coolest Mac designs of that era, but it’s also one of the first examples of the Jobs-era Apple putting too much emphasis on form over function.

It’s hard to argue that the acrylic cube is one of the most artistic industrial designs that Apple has ever come up with, and it looked beautiful on a desk. Sadly, that sleek aesthetic was mostly skin-deep.

The clear acrylic case contained all the internal components save the monitor, keyboard, and speakers, but that elegant look was lost as soon as you needed to hang any other accessories off of it. More significantly, however, the casing easily showed “mold lines” that looked more like cracks, detracting significantly from the museum-piece quality of the design.

It also wasn’t upgradeable. At all. There were no PCI slots, and you had to buy the monitor separately. While that sounds a lot like today’s Mac mini, the cube was priced more like a Mac Pro.

The G4 Cube sold fewer than 150,000 units and stayed on the market for less than a year. Recently, Tim Cook called it a “spectacular commercial failure, from the first day almost,” but also used it as an example of how fast Steve Jobs could “abandon even a product dear to his heart.”

The iPod Hi-Fi (2006)

Riding the wave of the iPod’s popularity, Apple decided in 2005 that it was time to throw its hat into the iPod speaker market, so it hired an engineer from Klipsch to produce its first dockable speaker for the iPod.

The iPod Hi-Fi wasn’t a bad product, but it was perhaps the first truly niche product of the iPod era. Apple’s speaker entered a world that was already dominated by many other Dock Connector capable speakers from Altec Lansing, Bose, JBL, Klipsch, and others, yet it didn’t offer anything that was compelling enough for most buyers.

In fact, for many, the iPod Hi-Fi just had too many limitations. Apple succeeded in its goal of providing a seamless experience for iPod users, with no power buttons or other controls to fuss with, this also meant that it lacked things like independent bass and treble controls. The only port on the back was a 3.5mm audio input jack, but there were no data or video out ports to allow you to sync your iPod or play movies and TV shows on your screen.

While it was one of the highest quality “portable” speakers available at the time, since it could run on a set of six D-cell batteries, with a weight of 17 pounds it was better described as “luggable” than “portable.”

To be fair, the iPod Hi-Fi did produce impressive sound quality at high volumes — Apple said it was built for a ten-foot listening experience — however its overall sound quality didn’t justify its high price tag over the competition, and Apple’s claims of “audiophile” sound quality were met with derision by many actual audiophiles. At $349 it was more expensive than most of the iPods you were supposed to connect to it, and it was discontinued in 2007 after less than two years on the market.

The Third-Generation iPod shuffle (2009)

In 2005, Apple diversified the iPod lineup with a new ultraportable player known as the iPod shuffle. The idea was to create a simplified player for those who just wanted to carry around a single playlist of a few hundred tracks in their pocket and listen to them in any order. Hence, the name “shuffle.”

The original iPod shuffle looked much like a USB flash drive with buttons. By 2006, the second-generation version had changed that up to the classic look the most of us are familiar with — a small rectangular device with a round set of controls that closely resembles the modern-day Siri Remote.

There was one significant outlier in the middle of this, however, in the form of the 2009 third-generation iPod shuffle. In what we can only assume was an effort to go as minimalist as possible, Apple’s engineers and designers got too clever for their own good. The result was a nearly buttonless device that was needlessly complicated and required the use of Apple’s own headphones — or an expensive third-party adapter.

Specifically, in its effort to get as small as possible — the 2009 iPod shuffle looked like a piece of chocolate — Apple moved all the controls onto the headphones. The only control on the body of the unit was a three-position switch to choose between off, repeat, and shuffle modes. Pausing, playing, adjusting volume, and skipping tracks all required you to use the controls on the headphones.

This meant that using your favourite headphones was out, as was connecting it to your car stereo or another set of speakers. Third-party adapter cables eventually came along, but these had to be licensed under Apple’s Made-for-iPod (MFi) program, adding to the overall cost of using your favourite earphones with your iPod shuffle. By 2010, Apple had abandoned this idea and released the fourth-generation iPod shuffle, returning to the classic design of the 2006 model, with a smaller footprint.

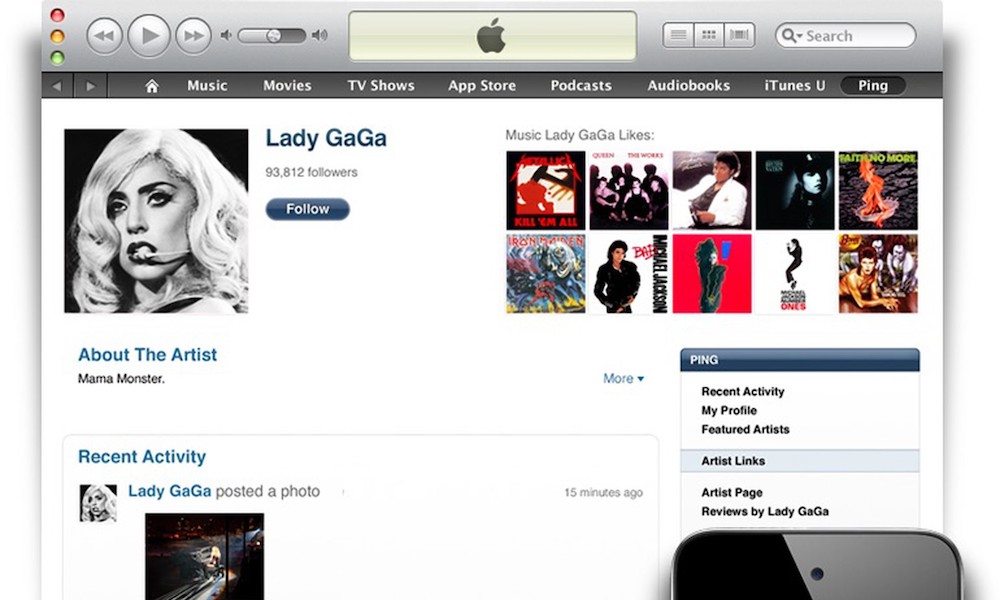

Ping (2010)

Back in 2010, the world of social media was exploding, and Apple clearly decided it wanted in on the action. With iTunes still being the most popular music platform back then, the company figured that it could capitalize on that by making the listening experience more social, and Ping was born.

When Steve Jobs introduced it, he described it as “Facebook and Twitter meet iTunes,” which was fair, except that people already had Facebook and Twitter, and most weren’t interested in signing up for yet another social network just to share their listening tastes and connect with their favourite artists.

To be fair, Apple wasn’t the only company trying to get in on the social media game back then, although it was the most high-profile company to fail to even get off the runway. Google launched its ill-fated Google+ social network around the same time, but at least that gained a pretty solid fanbase before finally getting shut down a few years later.

Dozens upon dozens of other small developers also attempted their own social networks, often tied to iPhone apps, but they all faced the same problem that Apple did: You can’t just build these things and expect people to show up, especially when all their friends are already hanging out elsewhere. After all, the most important thing for a social network is that it actually be “social.”

Ping ultimately became another big echo chamber, and Apple killed it off in 2012, saying that its customers had spoken, and the company just wasn’t willing to keep putting energy into building a place where nobody actually wanted to hang out.

The iPhone 5c (2013)

As mainstream iPhones started to become more premium devices, Apple decided to test the waters back in 2013 by offering a more “fun” low-cost iPhone that it hoped would be a hit with younger customers and others who couldn’t afford the more expensive iPhone 5s, or simply weren’t willing to shell out that much money.

The result was the iPhone 5c, which was basically a re-imagined version of the 2012 iPhone 5, dropped into a plastic shell and offered in five different colours.

This was actually Apple’s first attempt at selling the iPhone in anything other than basic black, grey, white, and silver colours, but sadly, it failed to gain any real traction. The plastic casings weren’t even as nice as those used on the 2008–2009 iPhone 3G/3GS models, and were definitely a big step down from the more elegant designs of the iPhone 4/4S and iPhone 5 that had come before.

It was also still “last year’s model,” and yet, it sold for only $100 less than the iPhone 5s, which offered a 64-bit A7 chip and a Touch ID sensor. This put it above the price of most other similarly equipped Android smartphones.

Apple also tried to put such a positive spin on the fact that it was made from plastic — even going to far as to use the phrase “unapologetically plastic” in its marketing videos — that it backfired. It ultimately sounded like it was trying too hard, and the design really did seem to go against its core brand.

Fortunately, Apple learned its lesson from the iPhone 5c. Later wallet-friendly iPhone models either used tried-and-true designs that had already proven their appeal, like the original iPhone SE, or they simply scaled down the features of current models while offering the same base specs, like the iPhone XR.

The HomePod (2018)

If there’s one area where Apple clearly didn’t learn a lesson from its past, it was with the original HomePod, which made many of the same mistakes that plagued the iPod Hi-Fi.

Announced at WWDC 2017 and released in early 2018, the HomePod was an expensive smart speaker with a very impressive set of features that most people didn’t really want, need, or care about.

Rather than following the iPhone playbook and creating a product that appealed to the masses, Apple went in the opposite direction with the HomePod, creating a speaker for hardcore Apple fans who also happened to be audiophiles. It turns out that’s a very tiny Venn diagram intersection.

To be fair, the HomePod was an incredible feat of engineering, but it addressed a set of needs that most people didn’t have. It was too expensive to be merely a smart speaker, and too limited to really be embraced as a premium speaker for audio enthusiasts.

Basically, you had to be completely immersed in the Apple ecosystem to even consider getting a HomePod. Unlike every other speaker in its price range, the HomePod didn’t work with Bluetooth, nor did it even feature a wired audio input. The only way to get music out of it was to either call up Apple Music with Siri or use AirPlay from your iPhone, iPad, or Mac.

It appears that Apple finally realized this last fall, giving up on the “great sound” part of the equation and releasing the $99 HomePod mini to function primarily as a smart speaker instead. By all reports, these have been selling like hotcakes, as they still provide good sound for the price, and they’re cheap enough to be an impulse buy for many iPhone users rather than a budgeted purchase.

Apple discontinued the full-sized HomePod earlier this year, perhaps ironically, just before it added new features to the 2021 Apple TV 4K that made the smart speaker considerably more useful. While there are reports that another premium HomePod is in the works, we’re not sure Apple has decided what form that’s going to take yet.